Wellness & Equity Education

Emergency Contacts

Regional Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Treatment Program

Staffed 24/7, St. Joseph’s Hospital, London (directions)

519 646-6100 ext 64224

Western Special Constable Services

Lawson Hall, Rm. 1257 (24/7)

From a campus phone: call 911 or x83300 (non-emergency line)

From a cell phone: call 519-661-3300

*For reports of gender-based violence, WSCS will connect you with the local police service.

Important Contacts

Gender-Based Violence & Survivor Support Case Manager

519 661-3568

support@uwo.ca

Anova (formerly Sexual Assault Centre of London)

24 hour crisis & support line:

519 642-3000

CMHA Crisis Centre & Reach Out

24/7 Crisis and Support Services

In person: 648 Huron St, London (directions)

Phone: 519 433-2023

Webchat

Human Rights Office

519 661-3334 (non-emergencies only)

Residence Counselling

Ontario Hall, Room 3C10

needtotalk@uwo.ca

Independent Legal Advice for Sexual Assault Survivors

Survivors of sexual assault may be eligible for up to four hours of free, confidential legal advice.

Indigenous Wellness Counsellor

Zhwwanong 24 Hr Emergency Women's Shelter for First Nations women and their children

256 Hill St, London, Ontario

Phone: 1-800-605-7477

Trans Lifeline:

877-330-6366

Gender-Based Sexual Violence Education FAQs

*for specific FAQs on incoming GBSV student training, click here.

General Concept Questions:

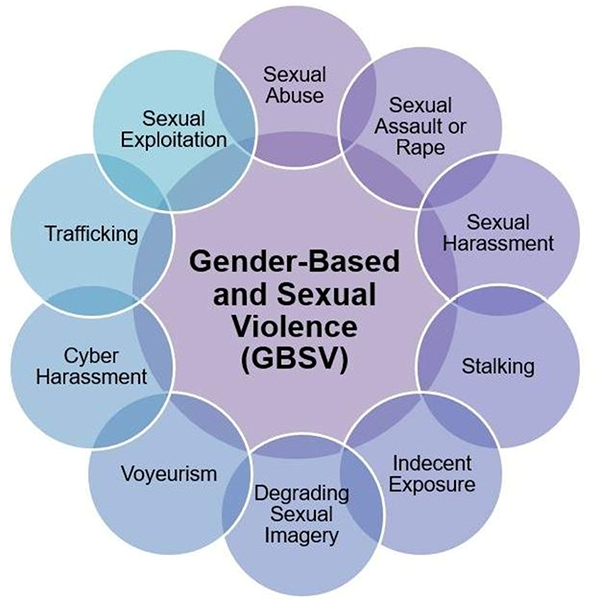

What is gender-based and sexual violence?

Any sexual act or act targeting a person’s sexuality, gender identity and gender expression, whether the act is physical or psychological in nature, that is committed, threatened or attempted against a person without the person’s consent, and includes sexual assault, sexual harassment, stalking, indecent exposure, voyeurism, cyber harassment and sexual exploitation. Gender-based violence also includes domestic violence, physical abuse, emotional and psychological abuse, and financial abuse.

On our campus, GBSV can look like: misogynistic signs at Homecoming, professors sexually harassing graduate students, assaults in residence, sexist chants during O-Week, and more.

| Around one third of participants reported they had witnessed or experienced gender-based violence on campus in the past year (GBSV UWO Report.pdf | Around 1 in 5 undergraduates and 1 in 10 graduate/professional/post-doctoral students reported usually feeling unsafe or very unsafe on campus. Students who identified themselves as gender diverse or as female were considerably more likely to report feeling unsafe | Women with a disability were nearly twice as likely as women without a disability to have been sexually assaulted in the past 12 months |

| Over 93 percent of reported sexual assault adult victims are female and 97 percent of accused are men. | 82 percent of sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows - a friend, acquaintance, date, teacher, family member, professor, advisor or coach. | Lesbian and bisexual women are 3.5 times more likely than heterosexual women to report spousal violence. |

What is consent?

Consent is an agreement between 2 or more people to engage in sexual activity (kissing, touching, having oral/vaginal/anal sex, grinding, sexts, etc.). An individual must actively and willingly give consent to sexual activity. Sexual activity without consent is sexual assault.

Consent:

- Is never assumed or implied

- Is not silence or the absence of "no"

- Cannot be given if the victim is impaired by alcohol or drugs, or is unconscious

- Can never be obtained through threats or coercion

- Can be revoked at any time

- Cannot be obtained if the perpetrator abuses a position of trust, power or authority

Consenting to one kind or instance of sexual activity does not mean that consent is given to any other sexual activity or instance. No one consents to being sexually assaulted.

| Look Like | Sound Like | Feel Like |

|

|

|

How do you practice consent?

What is coercion?

Sexual coercion is the use of pressure, threats, or emotional manipulation to get someone to do something that they don’t want to do.

Coercion could sound like:

- Threats: If you don’t have sex with me, I will hurt you

- Pressuring: Please baby, please baby I need it

- Emotional Manipulation: If you don’t have sex with me, I will tell our residence that you are gay

What are some common myths and misconceptions about GBSV?

Misconceptions about sexual assault are often referred to as "rape myths" although they apply to the broad scope of sexual violence. Myths downplay the seriousness of sexual violence and confuse our understanding of what consent means. Unfortunately, they can also contribute to the social context in which survivors are reluctant to report, blame themselves for what happened or worry that they won't be believed. Myths can create a climate of victim blaming in which perpetrators are excused for their actions.

Rape myths can also prevent people from stepping in when they witness behaviors that could lead to a sexual assault. For example, a friend may observe a roommate pressuring someone to have sex and do nothing to intervene.

| Myth | Reality |

| Victims should dress/act a certain way to protect themselves from being sexually assaulted. | What a person wears, what they were drinking, and who they were hanging out with is never a reason to deserve sexual assault. It is the decision of the person who caused the harm, and never the victim. |

| Certain people ‘ask’ to be sexually assaulted because of their race, sexual orientation, or gender identity. | No one ‘asks’ to be sexually assaulted. Certain groups are more at risk for experiencing sexual assault because of their experiences of systemic and societal oppression, such as racism, classism, colonialism, ableism, sexism, homophobia/ transphobia and more. |

| Sexual assault cannot take place in a long-term relationship. | Sexual assault can take place in a long-term relationship. Even if you have consented to sex before, every time consent to sex is required. No one is obligated to have sex with someone. |

| Men cannot be sexually assaulted. | Men can be sexually assaulted, and 1 in 8 Canadian men experience sexual assault. Due to traditional views of masculinity, male survivors may be less likely to come forward and ask for help. Everyone, no matter their gender identity or expression, deserves access to support. (Source) |

| People make tons of false reports about sexual assault. | False reports of sexual assault are very uncommon. In rigorous research, rates of false reports are consistently very low, ranging from 2% to 10%. This is similar to rates of false reports for other crimes. (Source) |

| The victim does not remember what happened or reported it to the police, so they must be lying. | When someone is sexually assaulted, they have experienced a traumatic event. Due to that trauma, their brain may not remember all the details but that does not invalidate their experience. A victim may not feel safe, comfortable or ready to talk to the police at the time of their assault or ever, and it does not impact the validity of their experience. |

| It was not violent or penetrative sexual assault, so it was not sexual assault. | Sexual assault includes all unwanted sexual activity, such as unwanted sexual grabbing, kissing, and fondling as well as rape. Often the media shows a narrow depiction of sexual assault, but even if your experience does not look like that it is still valid. |

What is the role of alcohol and drugs?

Alcohol and drugs are one of the most significant risk factors for sexual violence on university campuses. While not a cause, there is a strong relationship between sexual violence and the use of alcohol or drugs. Over half of all sexual assaults on post-secondary students involve alcohol or drugs (Source: Antonia Abbey et al., "Alcohol and Sexual Assault," Alcohol Research and Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 25. No.1 (2001), 44.)

Alcohol is by far the most prevalent drug involved in drug-facilitated sexual assault. Alcohol is sometimes used as a deliberate strategy to impair the victim's ability to provide consent. A perpetrator may use alcohol (sometimes also mixed with other drugs) to intentionally incapacitate a victim. In other instances, a perpetrator may target an individual who is already visibly intoxicated.

Alcohol is also a risk factor for perpetrating sexual violence as it can increase a person’s risk of not noticing or respecting cues of consent or non-consent. Research has shown that people who are intoxicated are aroused by deterrents, angered by refusal and more likely to use force (Abbey, 2002).

Engaging in alcohol and drug use has risks, and so does engaging in sexual activity. When the two are combined, it is important for us to monitor our own level of risk to keep ourselves and the people who we are having sex with safe.

What is cyberviolence?

Cyberviolence is defined as aggresive, harmful behaviours that target someone's physical, sexual, psychological, or emotional well-being. It can include:

- Harassing text messages

- online harassment

- threatening

- blackmailing

- unwanted contact

- stalking

- doxxing (sharing someone’s information online without their permission)

- hate speech

- non-consensual sharing of intimate images, audio or video

- threats of sexual assault or death

Young women (age 18-24) are most likely to experience the most severe forms of online harassment, including stalking, sexual harassment, and physical threats (Pew Research Center, "Online Harassment", Maeve Duggan, 2014). Women who face multiple forms of discrimination, such as racial or cultural discrimination, homophobia, and transphobia, may be at increased risk of online hate and cyberviolence. While these experiences may be common, it is not acceptable and everyone has a responsibility to create safer digital spaces.

Cyberviolence can be perpetuated by strangers or those closest to us. Within abusive relationships, cyberviolence may be used as another form of control over the individual. Sometimes cyberviolence can take place in online dating platforms where perpetrators will pretend to have a romantic relationship with someone to get intimate photos/videos, which can then be used as blackmail. While these are just a few examples of how cyberviolence can occur, all forms of cyberviolence are unacceptable.

Even though cyberviolence takes place online, it has real-world implications. The impacts of cyberviolence can include social isolation, altering one’s behaviour to appease the person perpetuating the violence, depression, anxiety, stress and more. It is important to remember if you experience cyberviolence, it is not your fault. Everyone deserves to have their digital identity respected.

Here are some ways everyone can practice safer online interventions:

- Do not share your passwords, change passwords frequently and have strong passwords

- Delete your browser history frequently

- Disable location sharing

- Document or screenshot any abuse you experience to support your case

- Use your privacy settings on social media accounts to adjust who can see your content

- If taking or sharing intimate photos of yourself, remove any identifying features such as your face, noticeable tattoos, birthmarks, or personal photos in the background

If you are a student who has experienced cyberviolence, Student Support and Case Management can provide support and resources.

If you are in crisis, please call 911. Visit the Crisis Contact Information webpage for additional resources for urgent support.

For more information about ways you can practice safe online interventions through strong passwords, multi-factor authentication, and privacy controls visit Western’s CyberSmart website.

For more information about cyberviolence and tech-facilitated violence, check out the Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund’s report.

What are the effects of GBSV on survivors?

Gender-based and sexual violence is traumatic and can have significant and long-lasting physical, emotional, psychological, and academic consequences.

Physical Effects: unwanted pregnancies, reproductive problems, sexually transmitted infections, or sleeping too much/ too little. Acute injuries are not always immediately evident and chronic health conditions may emerge over time.

Emotional/ Psychological Effects: chronic stress, anxiety, depression, guilt, internalized blame, shock, fear, embarrassment, memory impairment, difficulty concentrating, losing interest in previously enjoyed activities, withdrawing from friends/family, substance use/abuse, or minimizing the event.

Academic Effects: feeling unsafe on campus, worried about seeing the perpetrator in common areas (such as libraries, residence halls, and classes), lower academic performance, withdrawal from clubs/school activities, choosing to suspend studies, transferring to another institution, or dropping out of school altogether.

Have a question not answered here?

Email us at gbsv.edu@uwo.ca. We would be happy to answer your question.