A mystical Himalyan artefact comes to Western Chemistry

For Averie Reinhardt and her undergraduate thesis supervisor, TK Sham, the bubbling glassware of the stereotypical chemistry lab gave way to a story of international intrigue as told through the molecular composition of a mystical object treasured by peoples of the Himalayan regions.

For Averie Reinhardt and her undergraduate thesis supervisor, TK Sham, the bubbling glassware of the stereotypical chemistry lab gave way to a story of international intrigue as told through the molecular composition of a mystical object treasured by peoples of the Himalayan regions.

While travelling in China’s Sichuan Province with his wife, TK Sham, of the Department of Chemistry at Western, found a jewellery store selling Dzi beads. Coveted by many, and believed to hold healing properties, these stone beads are held closely by their owners for generations. The unique markings on the beads are thought to occur naturally in the formation of the stone; as the markings become more complex, prices of the beads can soar to the tens of thousands of dollars. Sham bought a relatively inexpensive example and hatched a plan…

While travelling in China’s Sichuan Province with his wife, TK Sham, of the Department of Chemistry at Western, found a jewellery store selling Dzi beads. Coveted by many, and believed to hold healing properties, these stone beads are held closely by their owners for generations. The unique markings on the beads are thought to occur naturally in the formation of the stone; as the markings become more complex, prices of the beads can soar to the tens of thousands of dollars. Sham bought a relatively inexpensive example and hatched a plan…

“In my fourth year, I was looking for a thesis project that was completely different to what I’d been learning about in class. When I saw TK’s project looking into the chemical origins of a mystical bead, I couldn’t say no!” exclaims Reinhardt. Upon joining Sham’s lab, Averie had the latitude to devise experiments and discover the murky beginnings of the Dzi bead.

“In my fourth year, I was looking for a thesis project that was completely different to what I’d been learning about in class. When I saw TK’s project looking into the chemical origins of a mystical bead, I couldn’t say no!” exclaims Reinhardt. Upon joining Sham’s lab, Averie had the latitude to devise experiments and discover the murky beginnings of the Dzi bead.

“There are so many counterfeit beads so, of course, I wanted to understand what they’re made of,” explains Sham. The pair threw everything and the kitchen sink at finding out how these beads are made. “The real question was whether the beautiful markings were man-made or naturally occurring,” says Reinhardt. Using advanced analytical techniques, like scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and even the synchrotron at the Canadian Light Source, Reinhardt and Sham found a series of interesting features in the bead.

“On the surface of the bead were tiny holes – we called them etch rings. On the circumference of these etched rings were tiny holes with microscopic deposits of copper oxide,” explains Sham. The team also found that the bead was made of agate, a type of quartz, however there was an unexplained trace of carbon as well. “In the end, I think we came away with more questions than answers,” laughs Sham, “Such is the nature of science.”

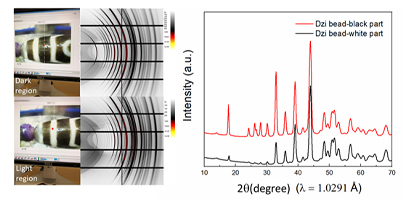

Figure 1

Figure 1 Caption

Grazing incidence XRD (middle and right panels) of the surface light and dark regions (red dot on the left panel) using 12 keV (1.03 Å) X-rays. Despite the intensity variation, the patterns are identical.

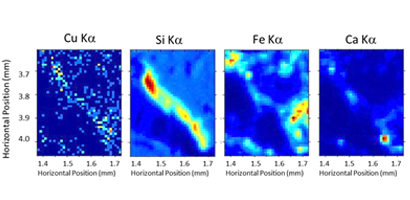

Figure 2

Figure 2 Caption

Cu K map of the ROI displayed in Figure 6 (d) compared with elemental maps of Si, Fe and Ca recorded in the same region. The Cu K XRF was produced by the second order radiation, 1460 eV, of 7130 eV. We can see that despite the weak signal in the Cu map, the coexistence of Cu and Si in the etched ring is evident.

The foray into the Indiana Jonesesque reaches of chemistry yielded no firm conclusion as to the provenance of the bead, but for Reinhardt, the experience was unforgettable. “Because we had no clue what to expect, I was allowed to design experiments and develop lines of inquiry,” she explains. This agency over the scientific process has left a lasting impression on the recent graduate; now working as a laboratory assistant in an environmental lab, she is contemplating a return to academia.

Sham is still chasing the secrets of the Dzi bead like Ahab sought the Whale. And the Dzi bead, shrouded in mystery, will continue its circuit from lab to lab, across Western Science.