First Year

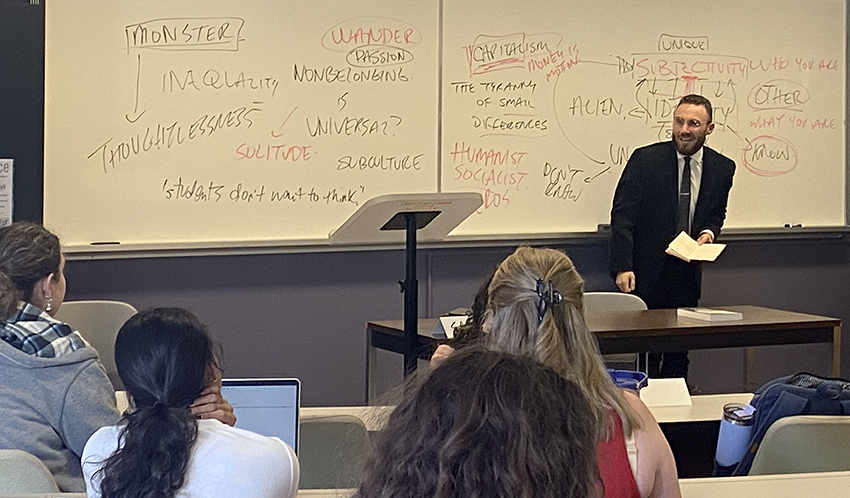

Teaching Assistant Tanner Layton leads a first-year seminar discussion on the role of the Public Intellectual

SASAH 1020E is taught by Research Fellows in the School. In lecture, discussion, and workshop formats, these faculty members will aid you in completing a variety of assignments, which might include traditional academic writing, creative work, and collaborative projects.

Our central purpose in immersing students in interdisciplinary dialogue and debate early on in the Program is to encourage you and enable you to take an active role in the future of the humanities.

The course has several objectives:

- to consider what it means to study “the Humanities” and how the Humanities needs to inform our understanding of our private and public roles. What is it to be human/inhuman, and what are our commitments as humanists?

- to reflect on the diversity of human experience, both current and historical, and the role of the intellectual in the world within the university and beyond it.

Prerequisite: Admission to the School for Advanced Studies in Arts and Humanities 3 hours/week, 1.0 course

Fall 2025

How might the arts help us to confront the urgent reality of climate change? What function might the humanities serve when the terms of human life seem increasingly precarious? Our approach to these questions will be anchored by two insights spanning climate science and climate activism: first, to mobilize meaningful climate action we must learn to navigate the pitfalls of polarization and individualism; and second, fostering collectivity depends on our capacity for conversation. For conversational models, we will look to leading climate communicators and activist groups, but also to artists, authors, scholars and organizers who have developed newly collaborative methods in response to ecological emergency. Drawing on these models, we will experiment with various communication and listening practices intended to establish common conversational ground in the classroom and beyond. This shared ground will in turn provide a platform for devising climate action projects that explore how best to integrate our climate commitments in everyday life.

Winter 2026

IntertextualityIn this course, we’ll explore the theory and practice of intertextuality: the ways texts respond to, transform, and reframe one another across time, culture, genre, and medium—and the ways, in fact, that it seems to be impossible for any of us to engage in ANY meaningful communication without connecting utterances with one another. In the broadest terms, we can accept, following Roland Barthes, “the death of the author”, and assert that every human production is “a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.”

We’ll trace the development of intertextuality theory/theories from the 1960s to the present day, but my primary interest will be in exploring how intertextuality works in practice. To help do so, I’ll draw on some of my own academic and personal interests, including Roman poetry, mediaeval manuscripts, and modern film and comics. I’m also currently interested in how intertextuality might help us understand some contemporary concerns: the nature of postmodern creative processes, the challenges of our post-truth culture and politics, the rise of generative AI, and our collective psychological shift from what Katherine Hayles calls “deep focus” to “hyper focus.”

But intertextuality is fundamentally about meaning emerging from webs of connections with no privileged, steady “centre”, so I hope that the meaning of this course will emerge collaboratively from our encounters with each other’s “mental archives” (Jessica Mason’s term for the sum total of stories that an individual has encountered over their lifetime).