Gardenship and State

Thinking with creativity

By Busra Copuroglu

How can artistic projects disseminate knowledge about complex socio-cultural and environmental issues? Conceived at the intersection of environmental critique, decolonial theory, and artistic practice, GardenShip and State engages this question to examine environmental catastrophe and its impact on the lives of colonized peoples by bringing together artists and scholars to mobilize knowledge through interdisciplinary work.

How can artistic projects disseminate knowledge about complex socio-cultural and environmental issues? Conceived at the intersection of environmental critique, decolonial theory, and artistic practice, GardenShip and State engages this question to examine environmental catastrophe and its impact on the lives of colonized peoples by bringing together artists and scholars to mobilize knowledge through interdisciplinary work.

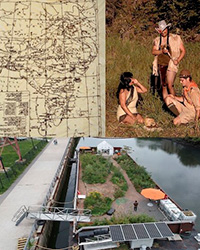

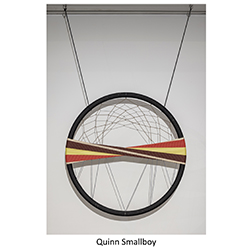

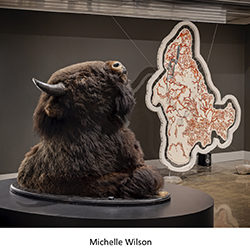

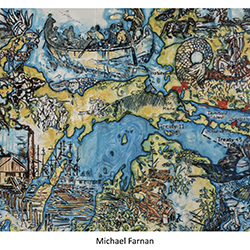

Led by Visual Arts Professor Patrick Mahon and in collaboration with artists, scholars, community partners, and student research assistants, GardenShip emerged from a four-year artistic research plan supported by Western’s Faculty Research Development Grant and SSHRC Insight and SSHRC Connections Grants. The first phase of the project has been showcased through the GardenShip and State exhibition at Museum London in 2021. Nominated by Museum London as an Ontario Galleries (GOG) Exhibition of the Year in 2022, the show was co-curated by Patrick Mahon and Indigenous artist Jeff Thomas. Bringing together 20 artists from across Turtle Island, Canada, and the U.S., the exhibition engaged the issues of climate change and decolonial critique. The second phase of the project, GardenShip Symposium & Community Gathering, which builds upon the exhibition, will take place on March 10 and 11 at Museum London.

Coming Together on the precepts of Haudenosaunee thought

The idea of garden and ship, in relation to colonization and the environment, goes back to Mahon’s earlier work, NonSuch Garden which engaged colonialism as a “fractured framework” and considered ships as carriers of European colonial ideologies to the new frontier. Then, over time, Mahon started to think about these issues within a more extensive project.

NonSuch Garden which engaged colonialism as a “fractured framework” and considered ships as carriers of European colonial ideologies to the new frontier. Then, over time, Mahon started to think about these issues within a more extensive project.

Mahon first planted the seeds of the GardenShip project by drafting grant applications in 2016. Around the same time, he approached Indigenous artist Jeff Thomas, whom he had met in the late 1990s on a jury for the Ontario Arts Council, to be co-curator. Some of the discussions on that jury, Mahon recalled, later became the basis of the project.

For Thomas, who received Ontario Arts Council Indigenous curator-in-residence grant for this project, the exhibition was his first curatorial experience with environmental issues. “My thoughts turned to what I had learned from my elders and to the precepts of Haudenosaunee thought as exemplified in the 1613 Two Row Treaty,” he said. “At that time, the Dutch colonists in what is now the area of Albany, New York, had begun expanding into Haudenosaunee territory. What eventually emerged was an agreement to live in peace and respect, and not to interfere with each other’s affairs.” Those precepts then came to be a basis for this project. “Patrick and I could bring artists from divergent practices and ethnic backgrounds into a cohesive forum to address the issues and challenges we all have to face in these challenging times,” Thomas explained.

An Interactive Experience and A Space to Think Together

The show at Museum London invited the audience to be active participants –-rather than being passive recipients—of the artworks. “In the exhibition,” Thomas said, “many of the works engage our senses with soundtracks and interactivity, and several installations ask us to walk around and through them making the show about much more than visual engagement with arts.” An interactive take-away journal specially created by project collaborators Tom Cull, Amelia Fay, Joan Greer, and Andrés Villar, and designed by Katie Wilhelm was given to visitors, encouraging them to record their impressions on the pages organized around exhibition themes. The show, Mahon added, presented “aesthetically rich, culturally complex artwork engaged in decolonial critique, environmental activism and protest against government and industrial complicity in the ongoing environment crisis.”

The show at Museum London invited the audience to be active participants –-rather than being passive recipients—of the artworks. “In the exhibition,” Thomas said, “many of the works engage our senses with soundtracks and interactivity, and several installations ask us to walk around and through them making the show about much more than visual engagement with arts.” An interactive take-away journal specially created by project collaborators Tom Cull, Amelia Fay, Joan Greer, and Andrés Villar, and designed by Katie Wilhelm was given to visitors, encouraging them to record their impressions on the pages organized around exhibition themes. The show, Mahon added, presented “aesthetically rich, culturally complex artwork engaged in decolonial critique, environmental activism and protest against government and industrial complicity in the ongoing environment crisis.”

The exhibition, Mahon explained, was not designed to dictate a message to the audience; instead, it aimed to invite the audience to interrogate and reflect on the realities that surround us. “We hoped that people would see the exhibition sort of under this sort of umbrella, a space within which we were able to wrestle with and face some of the realities that link our environmental crisis and that both history and present of colonialism,” Mahon said. “[This is] such a big project and kind of a heterogeneous group that we are not all working on one, a kind of discrete idea,” he added.

After the exhibition, the GardenShip team started to work on the exhibition catalogue to be launched at the Gathering. The 300-page catalogue designed by Katie Wilhelm features essays on the project themes such as women and colonization, plants and the environment, art, artifact and museums. Community project almanacs will also be distributed free at the event. Responding to the spirit of the project, these almanacs seek to confront the audience with some of the urgent questions that GardenShip examines: How can an almanac, which traditionally compiles seasonal information (i.e. meteorological, statistical) and collects localized knowledge, folk wisdom, and tips for the care of hearth and homestead, function when the parameters of seasonal forecasting are entirely made unpredictable due to climate change and when political and social upheaval disrupt concepts of hearth, home, and community?

About our Contributor

About our Contributor

Busra Copuroglu is a Ph.D. candidate in Comparative Literature with a background in French Studies. Her current doctoral dissertation, in progress, is about literary depictions of boredom and complaint from the late nineteenth century to the present.