Joshua Schuster

How to Think About Extinction

By Busra Copuroglu

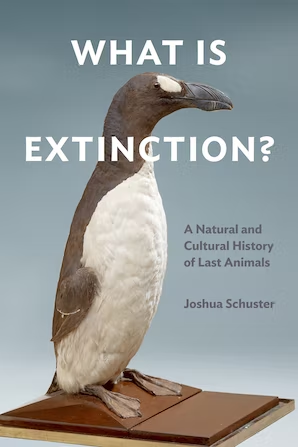

Joshua Schuster has been thinking a lot about extinction. The associate professor in English at Western, whose teaching focuses on the history of poetry, contemporary poetry, and environmental humanities, came at this work initially by looking at endangered animals in captivity. His curiosity about extinction over the last ten years has now culminated in his new book What is Extinction? A Natural and Cultural History of Last Animals, which came out early in 2023 (Fordham UP). In the book, Schuster takes up this foreboding question several times to offer close readings of various human and animal extinction events and examine different ways in which extinction was defined in critical moments and turning points in history.

Joshua Schuster has been thinking a lot about extinction. The associate professor in English at Western, whose teaching focuses on the history of poetry, contemporary poetry, and environmental humanities, came at this work initially by looking at endangered animals in captivity. His curiosity about extinction over the last ten years has now culminated in his new book What is Extinction? A Natural and Cultural History of Last Animals, which came out early in 2023 (Fordham UP). In the book, Schuster takes up this foreboding question several times to offer close readings of various human and animal extinction events and examine different ways in which extinction was defined in critical moments and turning points in history.

Throughout the book Schuster shows that extinction cannot simply be summarized as coming down to zero. In Schuster’s account, extinction appears as an event that has accrued different meanings in different contexts. To that end, his chapters focus on a variety of topics: critically endangered animals such as bison and tiger; the Holocaust and how Nazis tried to organize the animals and landscapes around things that were Germanic and things that were not; colonization, Indigeneity and narratives following the life of Ishi, an Indigenous man living in California who was known as “the last wild Indian in North America”; a close reading of the H.G. Wells’s 1895 novel The Time Machine, which features various encounters with extinction; de-extinction technologies that try to reconstruct genomes in laboratories to bring back lost species.

What drew Schuster the study of extinction? Schuster recalls the times he took his kids to the zoo. “I would see the tigers and wonder how they got there. How is it that there are so few tigers in the wild (~3,000) but so many (more than 10,000) in captivity?” he would wonder. The tigers we see in captivity, Schuster noted, are mostly in-bred or cross-bred and cannot be released into the wild. “So, if you want to understand what extinction [means] for tigers you have to understand what makes a tiger, tiger,” he said. “The tigers in the zoos are not in good physical and mental health. They walk back and forth; people think it’s their routine but it’s not. People should be thinking about this when they see the tigers in the zoo,” he added. Indeed, in the opening sentence of the book Schuster asks his readers to think about what he calls “melancholic knowledge,” the alarmingly low numbers of “iconic mammals”: 26,000 polar bears, 20,000 lions, 7,000 cheetahs, and 10,000 blue whales…

What drew Schuster the study of extinction? Schuster recalls the times he took his kids to the zoo. “I would see the tigers and wonder how they got there. How is it that there are so few tigers in the wild (~3,000) but so many (more than 10,000) in captivity?” he would wonder. The tigers we see in captivity, Schuster noted, are mostly in-bred or cross-bred and cannot be released into the wild. “So, if you want to understand what extinction [means] for tigers you have to understand what makes a tiger, tiger,” he said. “The tigers in the zoos are not in good physical and mental health. They walk back and forth; people think it’s their routine but it’s not. People should be thinking about this when they see the tigers in the zoo,” he added. Indeed, in the opening sentence of the book Schuster asks his readers to think about what he calls “melancholic knowledge,” the alarmingly low numbers of “iconic mammals”: 26,000 polar bears, 20,000 lions, 7,000 cheetahs, and 10,000 blue whales…

Halfway through the project, however, he realized that the extinction of animals could not be studied without discussing the humans involved, not only in the disappearance of animals but also with violence towards each other. “This is something so important to the whole planet and I wanted to learn about it and teach myself. There is a mentality of extinction that has been coming up in different historical instances,” he remarked. Over the course of his research, Schuster found that historically, people used the language of extinction in different ways. “Sometimes it was used to discuss animals disappearing and other times in violent historical and political ways, to colonize Indigenous People, for example. So, I wanted to see how people used the term extinction in different contexts,” he explained.

Schuster’s work on extinction also led to the publication of another book on existential risk, Calamity Theory: Three Critiques of Existential Risk, which he co-authored with Derek Woods, an assistant professor of media studies at McMaster University. Existential risk is a field of study that examines various planetary extinction events, and Schuster first intended the topic to be a chapter in What is Extinction? However, in the research process, realizing that there was more to say about existential risk than what can be contained in one chapter, Schuster decided to turn it into a book on its own. These two books, Schuster said, are now in conversation with each other. “Whoever wants to read them, I hope they also feel like they can contribute to the conversation on extinction,” he remarked.

Interdisciplinary Thinking, Extinction, and the Humanities

Schuster believes that we need more interdisciplinary thinking to address the rising extinction events on the planet in the contemporary moment. “We need to use humanities tools, science tools, and philosophical tools. If technology is doing all the work of defining, it’s not enough. Technology, science, and computing risk changing the meanings of extinction without including and collaborating with humanities, local communities, and Indigenous communities,” he explained.

The same interdisciplinary thinking, Schuster added, is also necessary to address AI. “AI is often produced in narrow, entrepreneurial situations,” he remarked. For Schuster, the understanding of AI should go beyond the level of programming. “We should also ask what it means, how it is used, and how it can be shaped. How to design AI to avoid any sort of extinction outcome, is the basic question that people driving these technological inventions should be asking,” he said.

ChatGPT and the Future of the Humanities

As anxieties around how AI and ChatGPT are going impact higher education –especially literary studies— continue to grow each day, Schuster, however, does not believe that literary studies are going to become extinct because of ChatGPT’s ability to produce writing. “I think it’s the exact opposite,” he said. “I think people who can think for themselves and not reproduce what ChatGPT does will be even more valued and rare [because] good reading and good writing is a [skill] that is hard to develop [and] it’s becoming increasingly rare,” he explained. These skills, Schuster argued, will be extremely valued because “if most people in the room can’t do good reading and good writing then the ones who can are going to [standout]. And this is what we focus on in the English department.”

Further, Schuster remarked, Humanities is a field that always needs to reinvent itself. “Most other fields and disciplines don’t have to question themselves over and over again, and it’s a good thing that we need to do that because it leads to creative projects, new ways of doing research and teaching,” he explained. “So, it’s not necessarily the worst thing to be in crisis,” he added. In fact, crisis, Schuster believes, is where thinking, learning, and new discoveries happen. “Nobody is exactly sure what it’s going to look like in 50 years and that’s good because we have a chance to shape it; we can all contribute to whatever this future thing called the Humanities will be,” he said.

The Value of the Humanities and Interdisciplinarity

Schuster also sees a future where the skills developed in the Humanities departments are going to become more relevant to address the questions around AI, extinction, and animal life. “We can both be interdisciplinary and learn from other fields and use the Humanities tools and extend them to other fields,” he said. “Being creative and analytical at the same time [is the] single most important skill to succeed anywhere in life,” he added.

The practice of close reading, for instance, Schuster said, is very valuable and can be applied to different contexts and disciplines. “There is also a huge value of tradition of close reading of novels and poems...That’s why I said I’m close reading extinction—reading extinction in terms of biology, conservation science, philosophy, and technology and also in literature,” he explained. “A good focus on a poem, or novel is deeply transformative for people who prioritize that because it’s a special moment. We live on a planet where there is the problem of draining resources [and] reading a poem is the exact opposite; it's always renewable, it doesn’t drain your resources, it gives you more thought and engagement and there are a few things in the world that can do that,” he added.

Schuster is now extending his interest in extinction to outer space. “Thinking about extinction should also be a thinking about life outside Earth,” he said. Next year, he is going to teach a graduate course on aliens, a topic that has been coming up in some of the essays published. He is also currently editing a book on American poet Will Alexander, whose work speaks to his preoccupation with extinction. “His poetry has a lot of cosmological language and multi-species encounters and is full of different kinds of life interacting with each other.

"Alexander’s poems show what a fuller biodiverse world looks like,” he said. It seems, while anxieties and theories about what the future on Earth will look like abound, the only certainty we will continue to face is the certainty of uncertainty.

About our Contributor

About our Contributor

Busra Copuroglu is a Ph.D. candidate in Comparative Literature with a background in French Studies. Her current doctoral dissertation, in progress, is about literary depictions of boredom and complaint from the late nineteenth century to the present.