Word of mouth lets medieval chants travel through time

In a world where people rely on smartphones and Google instead of memory, the spread of medieval chant is remarkable.

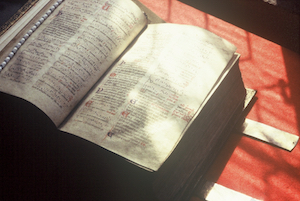

Medieval plainsong was often written in manuscripts such as this one, from the Lambeth Palace Library in England.

More than 1,000 years ago, an order of monks travelled across Europe, sharing thousands of plainsong chants in church services. The monks did not write their music down at first and relied on memory to replicate the intricate melodies, which flowed in a strictly oral tradition from person to person. Only much later did the chants appear in musical notations in liturgical books.

Musicologists believe some 30 million liturgical books were produced during the Middle Ages, and an estimated 10 per cent still exist. Cataloging these books is an immense task that requires time, effort and an expert knowledge of medieval chant. That work is being simplified by the very computer power that replaces memory today, driven by a project at Western University in London, Ontario.

“Traditional chant studies have typically been done by a single scholar, who spends significant time studying deeply to synthesize consistent findings or find obscure outliers,” says Dr. Mark Daley, Associate Vice-President (Research) and an associate professor in the Computer Science, Biology and Statistics & Actuarial Science departments at Western.

“While human knowledge and intuition are excellent, that approach is hampered by the fact that humans have to eat and sleep and have limited time for travel and research,” he continues. “With a computer, you can ask a question about 2,000 chants and get answers as fast as hitting the return key. My hope is that we’ll gain insights into chants – and the human memory – that are only accessible when we combine both of those scholarly traditions.”

Dr. Kate Helsen, assistant musicology professor at Western’s Faculty of Music.

Daley is collaborating with Dr. Kate Helsen, assistant musicology professor with Western’s Faculty of Music, who is excited about using computer analysis on the chants.

“Thanks to the late Andrew Hughes, a medieval musicologist and professor at the University of Toronto, we have more than 5,000 melodies that were lost to the human memory that once housed them, and no one living in our times has ever been able to compare them before,” she says.

The project expects to answer questions that are relevant for musicologists, who have been working on the same sorts of questions on a smaller scale for years. Does the way a melody begins dictate how it continues or finishes? How does the text relate to the music that sets it? More widely, these same types of algorithms could be applied to transcribe other kinds of music into modern notation to know how they sounded, for example, or to look at the underlying structure in poetry.

Medieval chant as a mysterious species

When medieval musicology was established in the 1860s in Germany, scholars heavily valued categorization, especially labeling, describing and tracking the evolution of pieces of music. Like biologists, they looked at a new “species” and asked, what could it do? Why it was found here and not there? What did it behave like?

The same direction marks the set of data being studied by Daley and Helsen, data carefully curated decades before by Hughes. Every summer throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Hughes drove through Europe with his wife and daughter, transcribing chants he found in manuscripts. A man ahead of his time, he saw the need to categorize, encode and preserve the chants in computer-readable form, although his early efforts crashed the university’s computers at least once.

“His transcriptions rescued thousands of melodies from the obscurity of medieval books, and some exist nowhere but his database and original archive,” Helsen says. “After he passed away in 2013, I was cleaning out his offices and didn’t want this treasure to get buried with him.”

Meanwhile, Daley had expressed an interest in meeting music researchers looking to collaborate with math/data scholars. He had studied music composition after high school before switching to mathematics and was still deeply interested in music. An amateur musician, he reads music and plays piano, harp and oboe.

“People interpret life through music, particularly in times we can’t understand, like death, birth and love,” Daley says.

Helsen agrees, “Rituals are both accompanied by and facilitated by music. Music connects us through the ages and reminds us of how finite our lives are."

Each dot represents a single chant melody, and the lines connecting it to other melodies represent how similar they are.

Daley notes, “Computer science has a lot of ways of gathering, storing and playing with data, and with this project, we found a way to do something really interesting with music. We’re now at a place where computers can use new methods and new lenses to look at huge amounts of data that have been painstakingly collected.”

After decades of obscurity, “It is time for the chants Hughes collected over a lifetime of scholarship to take their place in the spotlight,” Daley says. “It’s time for us to learn what they have to teach us about late medieval chant composition, both as idiomatic music and as the foundations of Western music history itself.”

Helsen says that in working with the encoding of the melodies done by Hughes, “We can already see that melodies are structured according to a kind of unwritten code. Some may link to saints, or denote a particular geographic region or a specific ‘composer.’ We can see where fragments of melodies appear in one part of Europe where they did not previously show up. We also gain insight into the capacity of human memory.”

Daley points out that the project shows the power of bringing together people with different expertise and from different disciplines.

“No one human can comprehend even a fraction of the knowledge that now exists in the world, and it will get worse with time. The only way to move forward is with teams from different scholarly traditions, interested in the same things but approaching research with different tools and insights.”