Fracking and Earthquakes: Western’s seismicity research seeks to minimize risks

When a 4.2 magnitude earthquake hit Fox Creek, Alberta in early January, it got a lot of media attention. That’s because the quake was caused by hydraulic fracturing – or “fracking” – the controversial practice of injecting fluids into deep shale to release oil and gas from the rock’s pores.

Fracking is widespread in the oil and gas industry, and versions of it have been in use since the late 19th century. But the technology has changed a great deal in recent decades, becoming invasive enough to produce small quakes by the late 20th century. And by the mid-2000s, the technology being used was generating more and more earthquakes.

Western University is leading the research into the seismic effects of hydraulic fracturing, with the goal of finding ways to evaluate and minimize the risks. The university initiated the Canadian Induced Seismicity Collaboration in 2013 with industry partners TransAlta Utilities and Nanometrics, under the auspices of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Since then, other universities and government organizations have joined, too.

The project is led by Dr. Gail Atkinson, the NSERC/TransAlta/Nanometrics Industrial Research Chair (IRC) in Hazards from Induced Seismicity in Western’s Department of Earth Sciences.

The project is led by Dr. Gail Atkinson, the NSERC/TransAlta/Nanometrics Industrial Research Chair (IRC) in Hazards from Induced Seismicity in Western’s Department of Earth Sciences.

“Before we started this,” she says, “the research on fracking was aimed at ways to maximize production volumes. But we look at the hazards and seek ways to protect the public, the workers and the environment.”

The Induced Seismicity Collaboration’s work is not anti-fracking, as evidenced by the range of universities, government and private-sector organizations involved. And most of the people who live in the fracking regions are also not against it, nor is the industry uncaring.

“In Fox Creek,” says Atkinson, “the entire economy of the town is dependent on the oil and gas industry. They don’t want the industry to go away, but they worry about the consequences of the larger events.” Those consequences could be significant, as Alberta and BC’s oil and gas regions have thousands of kilometres of pipelines, plus processing plants and other infrastructure that is not designed for earthquakes.

Dr. Burns Cheadle, of Western’s Department of Earth Sciences, is part of the Induced Seismicity Collaboration. Prior to Western, Cheadle was a geologist in the oil and gas industry for more than two decades.

Dr. Burns Cheadle, of Western’s Department of Earth Sciences, is part of the Induced Seismicity Collaboration. Prior to Western, Cheadle was a geologist in the oil and gas industry for more than two decades.

“In 2012, it was widely believed that you could not get earthquakes larger than a magnitude 2 or 3 from fracking,” he says. In fact, many researchers in the US still believe that the earthquakes are not caused by fracking, but by wastewater disposal, a lower-pressure, higher-volume process.

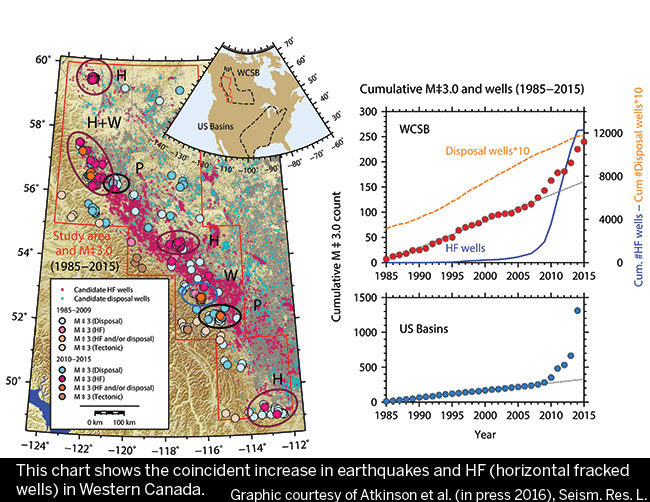

“Our work, however, is pointing to a different phenomenon in western Canada,” says Cheadle. “We have established a very strong statistical connection between hydraulic fracturing and the recent increase in the frequency of earthquakes in northwestern Alberta and northeastern British Columbia.” Cheadle adds that the earthquakes are happening at higher magnitudes, too, citing the August 2015, Fort St. John, BC quake that measured 4.6 – the largest fracking-related earthquake ever measured.

“Our data systems show us all oil and gas-drilling activities in Canada, and we can compare that to earthquake occurrence,” says Atkinson. “But we still have to be detectives; the quake might be due to a fracking operation, or might it be due to wastewater disposal, or maybe neither.”

To understand the processes, researchers need to be able to analyze a full range of seismicity data. However, the rich information that drilling companies collect from their own monitoring is a missing part.

“That data doesn’t become public because it includes embedded proprietary details, such as which techniques produce the best results,” says Atkinson. “The difficulty is in creating a protocol to allow the sharing of data, but at the same time protect the proprietary information of the companies collecting it.”

To that end, the Induced Seismicity Collaboration is working with the oil and gas industry with the goal of finding better ways to share information.

“Part of the science that we’re doing is to learn why it happens in some cases but not others,” says Atkinson. “And that is of interest to academics, regulators, and to industry operators, too.”

Dr. Atkinson is the Industrial Research Chair (IRC) in Hazards from Induced Seismicity and leads the Canadian Induced Seismicity Collaboration. Dr. Cheadle is a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences and is Director of Corporate Relations and Student Professional Development, Office of the Dean of Science. The Collaboration is funded by NSERC and two industrial partners, Transalta and the Nanometrics Corporation. University and government partners include the University of Calgary, the Alberta Geological Survey (AGS) and the Pacific Geoscience Centre (PGC) of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). Other collaborating partners include the University of Alberta and McGill University, as listed in Project Researchers.