Neuroscience & Music

About Dr. Jessica Grahn

Dr. Jessica Grahn is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Western University. She has established herself as an emerging leader in the field of the neuroscience of music which combines her unique background as a classically trained concert pianist and her training as a neuroscientist.

Dr. Grahn’s work stems from her interest in why we move to rhythm, and how movement and rhythm may be connected in the brain. She conducts brain scanning studies examining how different motor areas in the brain respond to musical rhythm. Dr. Grahn is also interested in how rhythm and music may be processed in the brains of those who have dysfunction in the brain areas that control movement, as happens in Parkinson's disease. Finally, she is intrigued why individuals vary greatly in rhythmic ability, and she is conducting behavioural and brain scanning studies to examine why there is such a striking range in the healthy human population.

Study Results

A study by Dr. Grahn (Grahn & Brett, 2009) found that Parkinson’s disease patients have subtle deficits in beat perception. That is, they have problems finding the regular, steady pulse that we tap our foot to when we hear a rhythm. The details of this investigation are below.

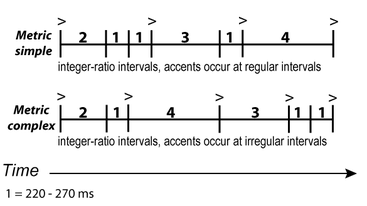

Rhythms from a previous study (Grahn & Brett, 2007) were used (see Figure 1). The metric simple rhythms (Listen to an example here - Example 1 ) are easier for most people to remember, because people feel a beat when they listen to them. The metric complex rhythms (Listen to an example here - Example 2 ) are similar, but don’t give a strong feeling of a beat, so people tend to do worse in remembering these rhythms.

During the investigation, Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy volunteers listened to 3 presentations of a rhythm. They indicated if the third presentation was the same as or different from the first two presentations.

Schematic example of the two types of rhythmic sequence stimuli used. Numbers denote relative length of intervals in each sequence. 1 = 220-270 msec (value chosen at random on each trial), in steps of 10 msec.

During the investigation, Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy volunteers listened to 3 presentations of a rhythm. They indicated if the third presentation was the same as or different from the first two presentations.

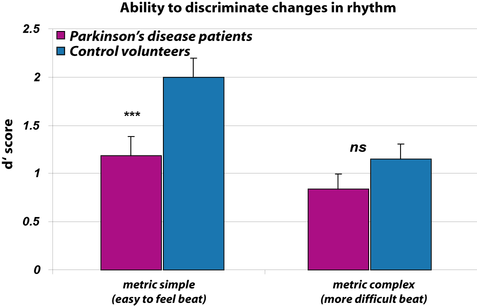

Dr. Grahn found that, compared to healthy volunteers, Parkinson’s patients had problems with beat perception. They were worse than control volunteers in detecting changes in the rhythms with a regular beat: the metric simple condition. This is shown on the left hand side of Figure 2: the pink bar is much lower than the blue bar. However, for rhythms without a beat (the metric complex rhythms), Parkinson’s patients’ performance was similar to healthy volunteers. This is shown on the right side of Figure 2. The pink bar is a little bit lower than the blue bar, but this was not significant: overall, Parkinson’s patients performed similarly to volunteers. This means that the Parkinson’s patients’ worse performance with metric simple rhythms cannot be because of a general problem at doing the task--their problem is specific to rhythms that have a beat.

Figure 2:

ns = not significantly different

*** = significantly different

Accuracy for patients and healthy volunteers on beat-based (metric simple) and non-beat-based (metric complex) rhythms. Patients are worse at detecting changes in beat-based rhythms, suggesting a problem in beat perception.

The Grahn Lab

Dr. Grahn and her lab are currently investigating the exciting prospect that music may have therapeutic benefits for patients with Parkinson’s disease. As the disease progresses in Parkinson’s patients, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to initiate movement. Music may stimulate the basal ganglia, making it easier for them to initiate movement (see video below).