Beauty is in the Microscope of the Beholder

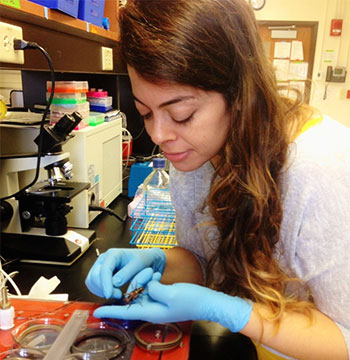

If someone told you that cockroaches are cute, how would you react? Many people would laugh. However, one student at Western University, Lauren Des Marteaux, a PhD student in Biology, sees the beauty in all insects, no matter their appearance, size, or function. Des Marteaux’s compassion for insects grew throughout her education and research endeavors. Des Marteaux holds a Bachelor in Zoology, and a Masters in Environmental Biology, both from the University of Guelph. Wanting to delve even deeper into the insect world, Des Marteaux came to Western to pursue her PhD studies, working under the supervision of Professor Brent Sinclair.

If someone told you that cockroaches are cute, how would you react? Many people would laugh. However, one student at Western University, Lauren Des Marteaux, a PhD student in Biology, sees the beauty in all insects, no matter their appearance, size, or function. Des Marteaux’s compassion for insects grew throughout her education and research endeavors. Des Marteaux holds a Bachelor in Zoology, and a Masters in Environmental Biology, both from the University of Guelph. Wanting to delve even deeper into the insect world, Des Marteaux came to Western to pursue her PhD studies, working under the supervision of Professor Brent Sinclair.

Des Marteaux’s research focuses primarily on understanding why insects lose homeostasis in the cold, and how some insects can maintain homeostasis in lower temperatures than others. “When insects are exposed to low temperatures, they enter a reversible state of paralysis called chill coma” says Des Marteaux, “They exhibit a loss of ion and water balance that is restored upon recovery.”

The threshold temperature for chill coma and loss of homeostasis varies across species and populations, but the cause of this variation remains unclear. Des Marteaux uses two species of field crickets as model insects, each varying in their threshold temperatures, thereby using natural variation in cold tolerance to get at these mechanisms.

The threshold temperature for chill coma and loss of homeostasis varies across species and populations, but the cause of this variation remains unclear. Des Marteaux uses two species of field crickets as model insects, each varying in their threshold temperatures, thereby using natural variation in cold tolerance to get at these mechanisms.

“Since insects do not thermoregulate, temperature has a profound effect on their performance and survival, and ultimately dictates their distribution” comments Des Marteaux. Des Marteaux recognizes that understanding more about insect thermal biology will not only leave us better-equipped to forecast their distributions in a changing climate, but may also have the potential to aid in the struggles of biological control for agriculture and public health. “Insects, like us, are just trying to get by,” says Des Marteaux, “They account for an enormous amount of biomass, and are arguably one of the most successful lineages of organisms in nature.” Insects not only survive, but they thrive, and we could learn a thing or two from them.

For Des Marteaux, she finds that “the exquisite diversity of form and life history made insects an irresistible group to study.” “Many researchers find immense beauty in the organisms they study,” says Des Marteaux, and researchers are drawn in by features most people would overlook. Not only does Des Marteaux find insects adorable, but she’s come to appreciate their significant ecological and economic roles. “Insects perform ecosystem services such as pollination, nutrient cycling, and food web support,” says Des Marteaux, “while also providing a direct protein source for nearly a third of the human population.” Insects aid in the decomposition of organisms and waste. Some insects even function as agents of biological control, which provide farmers and gardeners with effective and environmentally friendly pest regulation to maintain their crops. Wings, antennae, and stingers aside, it’s evident that insects play a substantial role in the ecosystem.

For Des Marteaux, she finds that “the exquisite diversity of form and life history made insects an irresistible group to study.” “Many researchers find immense beauty in the organisms they study,” says Des Marteaux, and researchers are drawn in by features most people would overlook. Not only does Des Marteaux find insects adorable, but she’s come to appreciate their significant ecological and economic roles. “Insects perform ecosystem services such as pollination, nutrient cycling, and food web support,” says Des Marteaux, “while also providing a direct protein source for nearly a third of the human population.” Insects aid in the decomposition of organisms and waste. Some insects even function as agents of biological control, which provide farmers and gardeners with effective and environmentally friendly pest regulation to maintain their crops. Wings, antennae, and stingers aside, it’s evident that insects play a substantial role in the ecosystem.