DLD Toolbox

Contact Us

Lisa Archibald, PhD

Associate Professor

Western University

School of Communication Sciences and Disorders

Elborn College

1201 Western Rd.

London, Ontario CANADA

N6G 1H1

Tel: 519-661-2111 ext. 82753

Email Dr. Archibald

Follow Dr. Archibald on twitter at @larchiba6!

DLD, Specific Learning Disorder, Specific Learning Disability: What's the difference?

by Lisa Archibald

DLD Diagnostics Flowcharts

- Volume 1: Diagnostic Statements for DLD

- Volume 2: DLD vs. Language Disorder associated with...

- Volume 3: DLD and Test Scores

- Volume 4: Co-occurring or Associated Language Disorder

- Volume 5: Identifying DLD in children under 5-year-old

- Volume 6: DLD, Specific Learning Disorder & Disability

Scenario: SLPs/SaLTs and educational psychologists are often asked to support children struggling to learn at school. Children with academic learning difficulties are often diagnosed with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) or Specific Learning Disorder, among others. In educational contexts, these children might also be described as having a Specific Learning Disability, a Speech and/or Language Impairment, or Speech, Language, and Communication Needs (SLCN), among others. How do all of these terms relate to one another?

Volume 6 of the #DLDToolbox addresses questions related to diagnoses and labels used to describe children with language and/or learning difficulties. Understanding a child’s difficulties in learning at school is an area that warrants multidisciplinary assessment. To name a few of the professionals involved, a SLP/SaLT provides information about a child’s speech, language and communication development. An educational psychologist assesses cognitive skills supporting learning. A classroom teacher makes important observations about how a child responds to general and specific instructional strategies. In reality, interprofessional collaboration is often limited due to constraints on time and resources. The aim of volume 6 is to support interprofessional collaboration by comparing terms commonly used to describe children with language and/or learning difficulties.

This blog turned out to be so long that I added some quick links here. You can jump to these sections of the blog by clicking on the link:

- Developmental Language Disorder and Specific Learning Disorder

- Co-occurrence of DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

- Overlaps between DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

- Key Differences between DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

- Educational Identification, Labels, Exceptionalities, Disabilities

- Specific Learning Disorder and Specific Learning Disability

- Educational Categories for DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

Let’s begin with the terms Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) and Specific Learning Disorder. These are both neurodevelopmental disorders, which are disorders with onset during the developmental period. Although the precise causes are unknown, it is assumed that each of these disorders are due to an interaction between biological and nonbiological factors. More specifically, these disorders are caused by multiple risk factors occurring together including the combined effect of many genes and many environmental factors.

DLD is a persistent language difficulty with a significant impact on everyday interactions or school learning not associated with a known differentiating biomedical condition (Bishop et al., 2016, 2017). The newest version of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, the ICD-11, now uses DLD in a manner consistent with this definition and without reference to mental age or intellectual functioning (https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f862918022). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM-5, uses the term ‘Language Disorder’ in a way that is consistent with DLD (http://deevybee.blogspot.com/2020/02/the-tldr-too-long-didnt-read-message-in.html). For both the DSM-5 Language Disorder and DLD, the diagnosis of intellectual disability would constitute a differentiating condition not consistent with either the DSM-5 Language Disorder or DLD. If an individual with an intellectual disability were found to have a language disorder, they would receive the diagnosis of ‘Language Disorder associated with Intellectual Disability’ (see #DLDToolbox volumes 2 and 4). For DLD, the language difficulties could impact any component of language including pragmatics (i.e., phonology, syntax, word-finding, semantics, pragmatics, verbal learning and memory) whereas the DSM-5 Language Disorder category does not include pragmatics. In the DSM-5, Social Pragmatic Communication Disorders are a separate category.

A Specific Learning Disorder refers to a persistent difficulty learning and using academic skills related to reading, spelling, writing and math (DSM-5). It is identified no earlier than 6 months after adequate instruction begins. The ICD-11 category, Developmental Learning Disorder, is largely consistent with Specific Learning Disorder except that the ICD-11 category retains cognitive referencing. According to the ICSD-11, affected academic skills must be markedly below expectations and general level of intellectual functioning (https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f2099676649). Although the ICD-11 lists separate disorders for reading, written expression, mathematics, and other patterns, the DSM-5 has one integrated category with specifiers. The category of Specific Learning Disorder lists specifiers for impairment in reading (word reading accuracy, reading rate or fluency, reading comprehension), impairment in written expression (spelling accuracy, grammar and punctuation accuracy in written expression, clarity or organization of written expression), and impairment in mathematics (number sense, memorization of arithmetic facts, accurate or fluent calculation, and accurate math reasoning). Further, the DSM-5 allows for 2 alternative terms. Described as one of the most common manifestations of Specific Learning Disorder, Dyslexia is suggested as an alternative term for problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor decoding and poor spelling abilities. Dyscalculia is offered as an alternative term to refer to problems processing numerical information, learning arithmetic facts, and performing accurate or fluent calculations. Although dysgraphia is commonly used to refer to disorders of writing, this term is not included in the DSM-5 as an alternative term.

Co-occurrence of DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

DLD and Specific Learning Disorder commonly co-occur. We know this because we know that DLD and Dyslexia (i.e., a Specific Learning Disorder) are different disorders (Bishop & Snowling, 2014) that commonly co-occur (Adlof & Hogan, 2018). Bishop et al. (CATALISE, 2017) suggested that an impairment affecting phonology only (and not other components of language) would be more characteristic of a literacy problem (i.e., Dyslexia) when involving phonological awareness and a Speech Sound Disorder when involving speech perception and/or speech production difficulties. It is estimated that about 50% of those with Dyslexia will also have DLD (Adlof & Hogan, 2018). This high overlap has led to calls for all children with Dyslexia to be assessed for DLD, and vice versa (Adlof & Hogan, 2018). According to the DSM-5, DLD and Specific Learning Disorder are potentially comorbid, but a dual diagnosis can only be given if a thorough assessment indicates each disorder independently interferes with daily activities including learning.

Overlaps between DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

We can expect DLD and Specific Learning Disorder to present similarly in many ways because they both impact academic learning across the educational curriculum. Language is the medium of instruction. Oral and written language is used for teaching, to provide content, and as a way for students to demonstrate their learning. Even academic subjects that seem to draw on other skills rely on language for learning. Take, for example, learning math. Many math tasks have high verbal demands including learning and switching between number symbols (e.g., five, 5), counting, arithmetic, and story problem tasks (Cross et al., 2019). As a result of these language demands, children with DLD often struggle across academic areas. Given that language is a foundational skill supporting learning, all children for whom there are concerns about academic progress or the learning of new concepts should be referred for a language assessment.

By definition, a Specific Learning Disorder in reading, writing, math, or some combination can be expected to impact academic progress across curricular areas. These are difficulties that are specifically related to formal instruction. The problems are not rectified by high quality classroom instruction, or even more intensive intervention targeting particular skills. The extent to which the learning difficulties are language-related should be carefully observed. Difficulties only in the context of verbally-mediated language tasks could point to DLD rather than a Specific Learning Disorder. On the other hand, a lack of response to instructions individualized according to a child’s language needs and targeted educational intervention of sufficient intensity would be reason to refer for an assessment of learning.

Key Differences between DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

Despite their potential overlap, DLD and Specific Learning Disorder differ in a couple of key ways. First, in terms of how the skills of interest are learned. DLD pertains to language learning. The human brain is predisposed for language acquisition, which means language learning happens largely without explicit instruction. We can assume the key processes supporting implicit language learning are impaired in DLD. In contrast, Specific Learning Disorder pertains to academic learning, which requires formal instruction, effort, and lots of practice. We can assume the key processes supporting explicit learning are impaired in Specific Learning Disorder. We must acknowledge that this distinction between language and academic learning processes is overly simplistic, and will be challenging to differentiate in practice. It is important that more research be done to determine how and if these two disorders can be differentiated.

Generally speaking, we can expect DLD and Specific Learning Disorder to differ based on when it is possible to detect the disorder. DLD is expected to arise early on in language development, whereas the first signs of Specific Learning Disorder will not be apparent until 6 months after formal instruction in reading, writing, and math has begun. The challenge here, however, is that when the disorder is diagnosed may be very different from when the first detectable signs of the disorder were available. For example, DLD often goes undiagnosed (McGregor, 2020) probably for a variety of reasons. Similarly, a Specific Learning Disorder may not be apparent until academic demands exceed the child’s academic learning capacities (see discussion nof disorder vs. disability below).

A final key difference between DLD and Specific Learning Disorder is in their relationship to oral and written language. As Snow (2016) so eloquently put it, language is literacy is language. As such, we can expect DLD to have an impact on both oral and written language. In older individuals, the language difficulties may be even more evident (or only evident) in written language tasks. Specific Learning Disorder, on the other hand, can be expected to impact written language to a greater extent than oral language. Children with Specific Learning Disorder might have difficulties in word recognition, reading comprehension, spelling, written composition, and math. Oral language impairments are not part of the Specific Learning Disorder diagnosis. Although there could be some oral language manifestations of a Specific Learning Disorder, these would be related to the lack of academic learning (e.g., poor vocabulary due to not reading) or overlap with academic skills (e.g., disorganized expression related to poor inferencing or metacognitive skills). Overall, the academic struggles should far outweigh any oral language weakness in Specific Learning Disorder.

Educational Identification, Labels, Exceptionalities, Disabilities

DLD and Specific Learning Disorder are medical terms; they are not educational terms. In many educational jurisdictions and countries, educational support is not provided based on a medical diagnosis (alone). Educational support is only provided if (and only if) the child has a disability or exceptionality requiring specially designed instruction including accommodations, modifications, alternative placements, or specialized services. Children with DLD or Specific Learning Disorder will usually qualify for an educational identification (or category or label) because of the impact of these disorders on the child’s ability to learn at school

It is important to appreciate the difference between the terms disorder and disability for this discussion. Disorder refers to a condition with a presumed biological origin but often for which no specific cause is known. Disability, on the other hand, arises because there is a mismatch between an individual’s capacities and the environmental demands or context in which the person is to function (Wehmeyer, 2013).

Specific Learning Disorder and Specific Learning Disability

Contrast, then, the two terms Specific Learning Disorder and Specific Learning Disability. Specific Learning Disorder refers to the medical determination of a persistent difficulty learning and using academic skills. A Specific Learning Disability, on the other hand, refers to the individual’s experiences of difficulties with the regular educational curriculum (e.g., difficulties with listening, thinking, speaking, reading, writing, spelling, or doing math). One key take away here is that Specific Learning Disorder and Specific Learning Disability are not synonymous, even though they are often used that way! Imagine, for example, a child with a relatively mild Specific Learning Disorder. That child might not struggle academically until later grades when academic demands exceed the child’s capacity. In this case, the child will have had the Specific Learning Disorder all their life (even if it wasn’t apparent until later grades) but only experienced a Specific Learning Disability when academic demands exceeded their capacity.

Definitions of Specific Learning Disability vary. Let’s take a close look at the definition from the U.S.A.’s Individual with Disabilities Education Act (2004):

Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. [IDEA, Section 300.8]

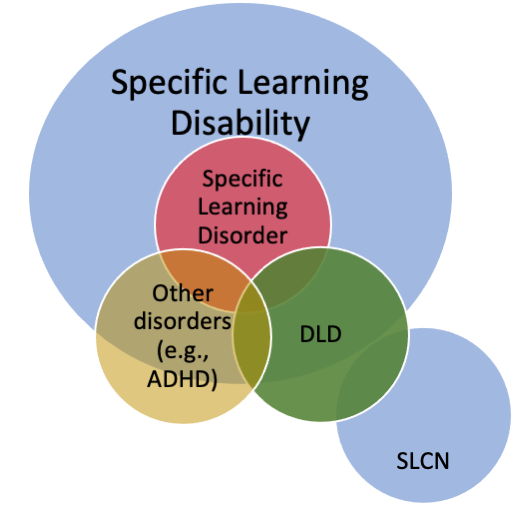

It is clear from this definition that a Specific Learning Disability can arise as a result of a many conditions, not just a Specific Learning Disorder. A Specific Learning Disability can also be a result of DLD (termed ‘developmental aphasia’ in the IDEA legislation), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (see https://sites.ed.gov/idea/idea-files/policy-letter-march-30-2001-to-colorado-department-of-education-special-education-director-dr-lorrie-harkness/), trauma, perceptual difficulties, among others. So, a child with DLD may experience difficulties with the regular educational curriculum, and be identified as having a Specific Learning Disability. A second key take away, then, is that DLD, Specific Learning Disorder, and other disorders can manifest as a Specific Learning Disability.

It should be noted that definitions of Specific Learning Disability differ across educational jurisdictions and countries. For example, in my province, the definition for learning disability includes cognitive referencing (‘academic underachievement inconsistent with intellectual abilities’, Special Education in Ontario, 2017). In contrast, learning disability and intellectual disability are used synonymously in the UK. Clearly these definitions vary widely, and in important ways! Please check the definition for (Specific) Learning Disability used in your educational jurisdiction and country in order to understand how it relates to DLD, Specific/Developmental Learning Disorder, etc.

Educational Categories for DLD and Specific Learning Disorder

Typically, a child with a Specific Learning Disorder will be identified in their educational context as having a Specific Learning Disability. Given that these 2 terms are often used interchangeably, it is likely that there will be no distinction in the process of identifying the disorder and making a determination of the disability.

The situation is not so clear cut for a child with DLD, however. There are some educational identifications (or labels) that are specific to speech and language (e.g., Speech Language Communication Needs (SLCN); Speech or Language Impairment). A child with DLD may be identified for services using any of these speech and language labels. As discussed above, however, a child with DLD is likely to experience difficulties with academic learning. As a result, many children with DLD will be identified with a Specific Learning Disability requiring educational support. There may be other categories or labels that are used in your area too (for example, in the US, children with DLD may receive services under the categories of ‘Developmental Delay’ or ‘Other Health Impairment’; https://dldandme.org/dld-in-schools-an-insiders-perspective/).

Here's a venn diagram where I try to represent how these labels all fit together! Thanks to my friend, Karla McGregor, for the suggestion. The blue bubbles represent educational identifications, labels, or categories. The red, green, and yellow circles represent the diagnosed conditions.

If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading to the end of this blog! These are complex issues! You will need to look carefully at the definitions and categories being used in your system, but I hope this volume will help you in coming to a fuller understanding of these categories. My hope is that this understanding will foster interprofessional collaboration.

References:

Adlof, S.M., & Hogan, T.P. (2018). Understanding dyslexia in the context of developmental language disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49, 762-73.

Bishop, D.V.M. & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental Dyslexia and Specific Language Impairment: Same or Different? Psychological Bulletin, 130, 858–888.

Bishop, D.V.M., Snowling, M.J., Thompson, P.A., Greenhalgh, T., & the CATALISE consortium. (2016). CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. 1. Identifying language impairments in children. PLoS ONE, 11(7): e 0158753.

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & the CATALISE-2 consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1068-1080.

Cross, A.M., Archibald, L.M.D., Joanisse, M.F. (2019). Mathematical abilities in children with Developmental Language Disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 50, 150-163.

McGregor, K. (2020). How we fail children with Developmental Language Disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51, 981-992.

Snow, P. (2016). Elizabethe Usher Memorial Lecture: Language is literacy is language – Positioning speech-language pathology in education policy, practice, paradigms and polemics. IJSLP, 18, 216-228.

Wehmeyer, M.L. (2013). Disability, disorder, identity. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51, 122-128.