News and Events

Contact us

Through the Administrative Office email Directory

or

Departmental Mailing Address:

Department of Biology,

Biological & Geological Sciences Building,

Western University,

London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5B7

Departmental Phone:

519-850-2542

Departmental Fax:

519-661-3935

Dr. Helen Battle Biography

August 31, 1903 – June 17, 1994

by Mitch Zimmer

Few people have been both a witness and a participant in Western’s growth as much as Dr. Helen Battle had been.

At the dawn of the 1920’s students from the Western University of London Ontario took their courses in a number of locations throughout the city. Often they would take street cars to attend classes in either a gymnasium on Oxford Street, the Old Peoples’ Home on St. James Street or even in a barn converted into a comparative anatomy laboratory at Huron College. One first-year student of this period was 16 year-old Helen Battle. She later recalled that the barn was owned by a jersey cow, “a nice doe-eyed beast with six per cent butterfat to her credit.” By the time she had completed her double medal winning work in both Botany and Zoology to earn her B.A. in 1923, the University had changed its name to the University of Western Ontario. As the campus was being consolidated on its present site in 1924, Battle was completing her work to be the first Master of Arts graduate from the Department of Zoology. Her thesis was in the field of fish embryology, an area which fascinated her throughout life and in which she probably made her greatest scientific contribution.

dawn of the 1920’s students from the Western University of London Ontario took their courses in a number of locations throughout the city. Often they would take street cars to attend classes in either a gymnasium on Oxford Street, the Old Peoples’ Home on St. James Street or even in a barn converted into a comparative anatomy laboratory at Huron College. One first-year student of this period was 16 year-old Helen Battle. She later recalled that the barn was owned by a jersey cow, “a nice doe-eyed beast with six per cent butterfat to her credit.” By the time she had completed her double medal winning work in both Botany and Zoology to earn her B.A. in 1923, the University had changed its name to the University of Western Ontario. As the campus was being consolidated on its present site in 1924, Battle was completing her work to be the first Master of Arts graduate from the Department of Zoology. Her thesis was in the field of fish embryology, an area which fascinated her throughout life and in which she probably made her greatest scientific contribution.

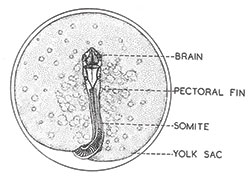

Battle went on to the University of Toronto to become the first woman in Canada to be awarded a Ph.D. in Marine Biology in 1928. When she returned to Western as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Zoology, her investigations not only spanned the traditional field work in marine biology but she was also one of the first to actively apply histological and physiological laboratory research methods to marine problems. She also pioneered the use of fertilized fish eggs to study the effects of carcinogenic substances on development. The penetrating insights of her published papers were often accompanied with detailed pen and ink drawings done by her own hand.

Biology in 1928. When she returned to Western as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Zoology, her investigations not only spanned the traditional field work in marine biology but she was also one of the first to actively apply histological and physiological laboratory research methods to marine problems. She also pioneered the use of fertilized fish eggs to study the effects of carcinogenic substances on development. The penetrating insights of her published papers were often accompanied with detailed pen and ink drawings done by her own hand.

During most of the summers between 1923 to 1941, Battle spent her time at the Fisheries Research Board of Canada in St. Andrews, New Brunswick and supplemented her research experience with stints at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Plymouth, England in 1935 and the Stone Laboratory at Put-in-bay, Ohio in 1937 and 1938. She published 37 articles between 1926 and 1973 ranging from studies of skate, mussels, hake and goldfish as well as papers on pedagogical methods in biology for secondary school students. She often worked in the confines of a very tight budget with limited resources. At one point the funding was so meager that instead of using traditional staining jars for histological preparations, her laboratory resorted to using marmalade jars.

During most of the summers between 1923 to 1941, Battle spent her time at the Fisheries Research Board of Canada in St. Andrews, New Brunswick and supplemented her research experience with stints at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Plymouth, England in 1935 and the Stone Laboratory at Put-in-bay, Ohio in 1937 and 1938. She published 37 articles between 1926 and 1973 ranging from studies of skate, mussels, hake and goldfish as well as papers on pedagogical methods in biology for secondary school students. She often worked in the confines of a very tight budget with limited resources. At one point the funding was so meager that instead of using traditional staining jars for histological preparations, her laboratory resorted to using marmalade jars.

Even though Battle was working in a male dominated profession, she said, “I was treated exactly the same as a man.” In 1949 she became a full professor. Her insight, tenacity, hard work, diplomacy and vision enabled her to take on many leadership roles. In 1956, the Head of the Zoology Department, Dr. Tony Brown was invited to work with the World Health Organization in Geneva for two years. Dr. Battle became the Acting Head of the Department during his absence. It was at this time when plans for the Biology & Geology Building were just beginning to be drawn up and she was responsible for the design of this building. She took this role very seriously and probably had more input in the layout of the original building than anyone else. In 1961, she was a founding member and first Vice-President of the Canadian Society of Zoologists. She then became the organization’s President in 1962 to 1963. In the 1970’s Battle took on the role of Associate Editor of the Canadian Journal of Zoology. “We’re very proud of this journal,” she said, referring to its physical appearance as well as its content. “It’s one of the nicest in the world.”

But it was Battle’s work as an instructor that drew the warmest response. She often said that teaching was her first goal. Her teaching career at the university began in 1921 as a demonstrator to pre-medical students. Throughout her career she taught classes in honors Zoology, Anatomy and Histology courses for nurses and an introductory course in Biology to a large number of arts students (who later recalled the rigors of ‘Bi.Sci.’ as their only science course). Her skills as an illustrator added a fuller dimension to her Embryology classes for the medical students as she would often render drawings in coloured chalk on the blackboard. Part of Battle’s success as a teacher derived from her own drive and enthusiasm for the subjects she taught and her expectation that students invest themselves in the subject as much as she did. At the same time she was gregarious and compassionate.

Battle maintained an interest in her former students who would often be seen visiting with her years after graduation. Even the children of former graduates would see her to talk about course selection or just to have a sympathetic ear to listen. “They come to me to talk over their problems,” she would say.

It has been estimated that in between the end of World War II and 1967 Battle had taught close to 4500 students. Those students included John Robarts, Premiere of Ontario and Nobel Prize nominee Murray Barr, discoverer of the “Barr Body” within cell nuclei. Of her teaching career Battle said, “I never felt that I was promoted or demoted because I was a woman.”

She had a deep interest in the advancement of female students. Battle encouraged women to go to graduate school at Mount Holyoke University and would often put in a good word for them.

Even after her retirement in 1967, Battle was engaged in finding innovative ways to teach. From 1968 to 1970 she was one of the first instructors to use the medium of television. A pioneering series of lectures were taped from  the lecture theatre in the Natural Science Centre. It was also during this period where Battle received a multitude of honors beginning with a tribute held on March 31, 1967 in the Great Hall. The testimonial was organized by the Department of Zoology where it was announced that a scholarship was established in her honor. Several hundred guests including former students from Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Vermont plus friends, relatives and colleagues were each remembered and warmly welcomed by her. During that same year, Battle received the Canada Centennial Medal and became an honorary lifetime member of the Canadian Society of Zoologists.

the lecture theatre in the Natural Science Centre. It was also during this period where Battle received a multitude of honors beginning with a tribute held on March 31, 1967 in the Great Hall. The testimonial was organized by the Department of Zoology where it was announced that a scholarship was established in her honor. Several hundred guests including former students from Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Vermont plus friends, relatives and colleagues were each remembered and warmly welcomed by her. During that same year, Battle received the Canada Centennial Medal and became an honorary lifetime member of the Canadian Society of Zoologists.

In 1971 Battle was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Western. During the convocation ceremony of May 27, President and Vice-Chancellor D. Carlton Williams said of Battle, “It is perhaps this undiminished zest and enthusiasm for her work, her students and her University that are her most distinguishing and, I suggest, her most endearing characteristics. Nor is it without significance… that an Irish colleen with a name like hers should vigorously support the enhancement of the status of women, a cause to which she brings a dazzling combination of charm, Machiavellian ingenuity and a whim of iron.” On October 30 of the same year, Battle received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Carleton University. In his citation Dean H. H. J. Nesbitt, Dean of Science at Carleton, made the following note about Battle’s research and teaching, “In all these areas she has more than enhanced the status of women; she has brought to all that dazzling combination of charm, devotion, and humanity that make her a ‘true apostle of women’s rights.’” It was also during this year she was made the Chief Examiner for Zoology for the Ontario Department of Education.

In 1975 Battle was selected as one of 19 outstanding women scientists by the national Museum of Natural Science and was represented in a traveling exhibit to mark International Women’s Year. The honors continued in 1977 as Battle was the first woman to be awarded the F. E. J. Fry medal from the Canadian Society of Zoologists and within a few weeks she received the first J. C. B. Grant award from the Canadian Association of Anatomists, a feat made even more noteworthy in that the Association is mainly made up of medical anatomists who recognized the importance of her studies to non-humans.