| DOUBLE DUTY CAREGIVING MODEL (2001) |

Health professionals who assume elder family caregiving responsibilities are located at the juncture of the public and private domains of caregiving, where they constantly negotiate the boundaries between professional and personal caring work. The conceptual model (2001) depicts the experience of double-duty caregiving. Study1 illuminated four inextricably linked components of double duty caregiving: 1) familial care expectations, 2) level of support, 3) negotiating strategies, 4) caregiving interface. The revised conceptual model (2011) depicts the experience of double-duty caregiving as well as the strategies employed by DDCs, "Professionalizing Familial Care: and "Striving for Balance". Familial Care Expectations

The expectations to care for aging relatives are especially strong for DDCs, the duality of the gendered expectations of women and family care combined with a professional background positions DDCs at the forefront of care. Expectations of self and others have a profound influence on the types of caregiving responsibilities and the care work assumed by DDCs.

Level of Support

Double Duty Caregivers receive varying degrees of emotional, informational, and instrumental support from family, colleagues, and community resources. For example, spouse and siblings/adult children play a critical role to help manage the care of an elderly relative. In addition to or in lieu of family supports some DDCs rely on colleagues to provide necessary support. For example, some co-workers ‘cover’ for short-term absences, or alter their schedules to help accommodate the double-duty caregiving demands. The presence or absences of suitable supports have a significant impact on how DDCs appraise their caregiving situations. Negotiating Strategies

A number of interrelated negotiating strategies, such as setting limits, using connections and delegating care, are used by DDCs either to limit the caregiving demands on them or to expand supports in order to manage increasing demands. For the most part, setting limits is often used by DDCs to help contain the expectations of family and professionals. Using connections is another strategy that DDCs employ to ensure that their family member receives quality care. In some situations, DDCs use their knowledge of the system and their professional status to acquire certain types of supports, such as home care services or consultations with specialists. A third strategy used by some DDCs is delegating care to paid professionals and/or family members. Recognizing that DDCs cannot provide all the care all the time, some ask others to take on some of ‘their’ caregiving responsibilities. Although these strategies were somewhat effective in limiting demands while increasing supports, especially in the form of instrumental help, it is apparent that the source of the demands, the types of caring work involved and the resulting blurring boundaries of care, involved multiple factors, both paid and unpaid. The context of caregiving needs to be considered when assessing how nurses’ access strategies. Caregiving Interface

The caregiving interface (connection between professional lives and personal lives of caregiving) varies for each person, depending on the degree of expectations of familial care and on the level of support available to manage multiple caregiving demands.

|

DDC PROTOTYPICAL EXPERIENCES |

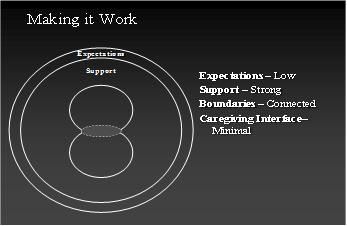

Findings from Study 1 (see Double-Duty Caregiving: Women in the Health Professions, 2005) suggest that there are three distinct, yet interconnected types of double duty caregiving experiences: Making it Work

The expectations tend to be low for these caregivers, partly because the care needs of the elderly relatives are not excessive. Requests for assistance are usually periodic, fall within the DDC’s domain of professional practice and require a small amount of time. DDCs who are experiencing ‘making it work’ are generally able to contain growing expectations and solicit any needed assistance, which usually results in a minimal blurring of boundaries.

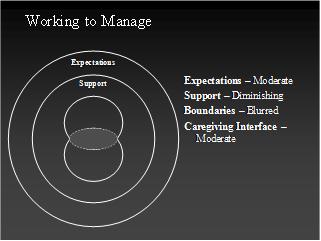

Working to Manage

The expectations tend to be moderately demanding, and for some gradually increase over time. Often these DDCs need to acquire more health information outside their area of expertise. In addition, families and other health care providers often expect them to assume more and more care and strategies for limiting care may not as effective.

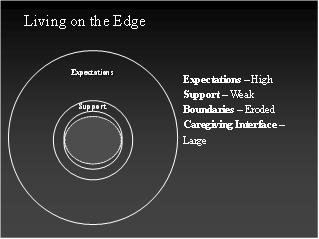

Living on the Edge

The level of familial expectations to provide complex, daily care can be exceedingly high. If family and workplace supports were previously present, they have weakened considerably. In addition to caring for their elderly relative, many DDCs provide emotional and instrumental support to other family members who lack health professional skills and knowledge. Boundaries between personal and professional caregiving become almost completely eroded. Many DDCs experience exhaustion and loss of self while they are ‘living on the edge’. |

This page was last updated on January 16, 2013