Your home? Your loved ones? Your pet? Or would you wait for the perfect sunset, a double rainbow, waves crashing into the shore? Or would you have someone take photos of you with your family?

And what if you couldn’t instantly see, change or delete your photographs for a retake?

What 24 shots would you take?

With cameras on our phones, digital photography and sophisticated photo correction software, rarely do we ever consider limitations such as this.

Thirty-four dialysis patients considered these questions as they documented their lives as part of the Renal Community Photo Project.

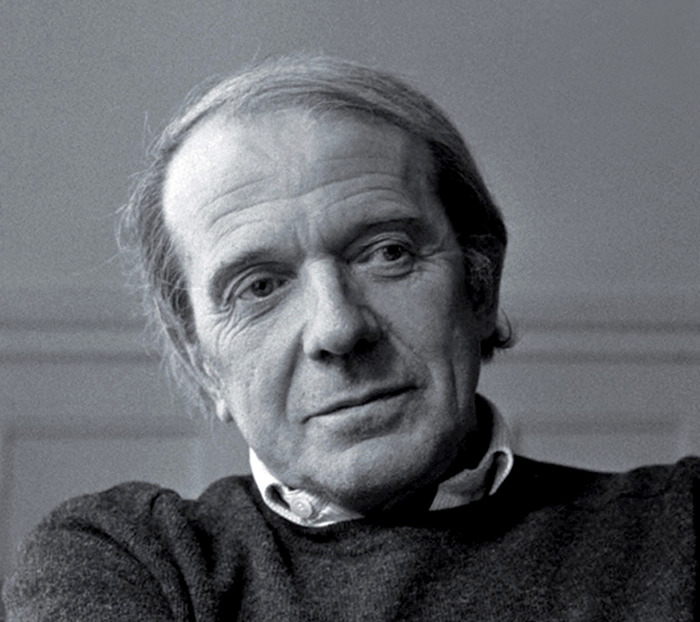

Dr. Christopher McIntyre

The Photo Project, led by Dr. Christopher McIntyre, engaged patients to use different types of cameras to share aspects of their lives with their clinicians.

Dr. McIntyre is a nephrologist and clinician scientist who is focusing aspects of his research on the harm that dialysis can have on the body. This includes understanding the damage it causes the organs and the stress it has on the cardiovascular system. Through research, Dr. McIntyre’s team has come to understand that dialysis causes recurrent brain injury, having an impact on people’s thought processes and moods. But they wanted to better understand how the damage that occurs in the brain affects the everyday lives of dialysis patients.

Dr. McIntyre also wanted to understand why some patients were experiencing depression, while others remained hopeful, outward looking and enjoyed rich lives even though they were experiencing similar physiological changes as those who were struggling.

“We needed to find a way to ask that question and listen to the answer,” said Dr. McIntyre. “It clearly wasn’t based on how long they were in the dialysis unit. So we needed a way to connect with them when they weren’t at the dialysis unit; we needed to find a way to get a glimpse into their lives.”

The team surmised that if they could understand where and how certain patients gained that resilience, it could it be transferable.

“We wanted to better understand so we could potentially inoculate that into those people who were struggling,” said Dr. McIntyre.

They chose to use a visual approach to the research, and more specifically, photography rather than a narrative approach because of the universality of the process.

Because it has the capacity to communicate before, or beyond, spoken or written language, there are many existing medical studies that use photography. The emotional pull and power of photos is also quite remarkable because of the insights and avenues into experience that it can offer to researchers and participants.

Seven years ago, while travelling in Brazil, Dr. McIntyre met a young photographer who had been working on a project taking photos of people living with cancer. The photos were displayed with the cancer cells projected on their bodies. The photographs made a strong impression on Dr. McIntyre. For him there was something so powerful about the images and what the people in them were saying about themselves. The idea of using photography to explain the human condition stayed with him.

As Dr. McIntyre searched for answers to his own research questions, he wondered if photography might serve as a vehicle for his work as well.

“It took me moving to Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and Western University, an institution which has sufficiently low walls between its different parts, to give me the confidence and navigation to walk into the Department of Visual Arts and ask about how we might collaborate and do our research project,” said Dr. McIntyre.

Thanks to a generous donation from a Western University alumnus in support of research related to patients with kidney disease, funding for the project was available.

Joy James, PhD, associate professor and former Chair of Visual Arts, was the first colleague Dr. McIntyre met in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities. Among James’ many areas of specialization are histories and theories of photography and visual culture, and her expertise took the team down an interesting and new path.

“One of the advantages to working with Visual Arts is that they introduced us to a different way of thinking,” said Dr. McIntyre.

Dr. McIntyre explained that for the most part medical research takes a Cartesean approach, where a question is asked, an experiment is conducted and if the researchers are lucky then the answer is perfect. In asking questions this way, you rarely get an answer that transcends your question.

Photo credit: Goodreads

James directed McIntyre and his team to consider the philosophical learnings of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze.

Deleuze propounded that creative thought was not linear but rhizomal like the roots of a plant. This means you can enter a process at any point and when you enter, you can exit at any point, but you don’t necessarily know where you are going to exit when you enter. Although more challenging at times to navigate, this process means that your answer can eclipse your question.

Using this philosophy meant the study was much more fluid than most medical research projects. The team specifically chose not to have any parameters set around the number of subjects, length of the study, themes for photographs, and a primary end point. This approach would become somewhat of a challenge for them when they began engaging and seeking ethics approval.

In the fall of 2016, the team submitted the Renal Community Photo Project for research ethics approval. Not surprisingly, the request which was undirected and non didactic was met with a seemingly endless number of questions.

“What is the primary end point?”

“How long will the study last?”

“What are you hoping to show?”

“How many participants will you have?”

"How will you maintain confidentiality for the patients given the intimate nature of the photos?"

Despite facing challenges in addressing some of the questions posed by research ethics, they were able to work through the details of the project, learning as they went. At the beginning of 2017, initial ethics approval was received and the project got underway.

Using an unconventional research approach and venturing into unknown territory, Dr. McIntyre pulled together a team of experts to work on the project.

The team was charged with creating a thoughtful process to engage patients, research and source different cameras that might be used, secure ethics approval, support research subjects and panelize, integrate and curate the images once they were received.

Cindy House is a Research Assistant at Lawson Health Research Institute, and worked closely with Dr. McIntyre on this project to provide all the operational support. Her most critical role was to form relationships with members of the renal community and support the nurses who engaged the prospective participants in the research study. She serves as the main contact for all participants and advanced the project through to the awareness stages.

Cindy House

Ruth Skinner, a PhD Candidate, brought the expertise from Visual Arts. Skinner’s area of expertise includes the histories and theories of photography and theories of representation and viewership, which would be critical as the team moved through this unique journey.

Ruth Skinner

Early on, Skinner was involved in researching and sourcing different cameras that might be introduced for participants. She was also involved in researching existing participant-centric studies that used photography, like the photo voice and the photo novella methods, so they could consider what elements they could use for this project. It also led to them choosing photography processes like cyanotype paper, pinhole photography and disposable cameras alongside digital and polaroid cameras.

Nurses working in the dialysis unit played a key role in making recommendations regarding which people they thought would be interested in the study and sharing it with the partners of other people who may not volunteer themselves.

As each of the 34 participants joined the project, they selected the type of camera or cameras they wanted to use, and were provided direction for using the camera they chose, as well as receiving an overview about the principles of photography and privacy considerations. They weren’t, however, provided with any direction on what photos they should take.

Participants were also given the option to write accompanying logs, which could be used to describe why they photographed what they did.

“We wanted to avoid providing directions or a shot list,” said Skinner. “We invited participants to photograph whatever they wanted to express about their lives.”

Within months of the project starting, an idea arose to bring the participants together in small groups to share their images, discuss their experience with the Photo Project, provide feedback on how they wanted to see their photos shared and to discuss more broadly their own journeys with dialysis.

“What we did was create a town square, where the participants could come together and connect with others who were having similar experiences,” said House.

Once ethics approval for this sub-study was received, participants were approached and those interested were invited to the discussions.

Skinner says that the addition of this phase of the research was important because, as an art-based study, the research process needs to remain participatory, reflexive and self-assessing at every stage.

"What we did was create a town square, where the participants could come together and connect with others who were having similar experiences"

Sitting in a room by himself for seven hours, Dr. McIntyre poured over the more than 1,500 photos that he and his team had received from the participants for several months.

“It was a really, really interesting day,” he said. “To see inside people’s minds and lives; it was a study in human nature.”

Many participants entered the study with caution, worried that they wouldn’t have anything interesting to share and apologetic that their photography skills were not strong enough to produce engaging photography. But they were encouraged to enjoy the process and in the end many participants expressed that taking the photos made them see and experience their lives differently.

The results really speak for themselves, with each photo telling a story.

As a clinician, Dr. McIntyre interpreted the images from a medical perspective.

“As I looked through the photos, I could see the scars on a participant from previous surgeries, I began to better understand the personal battles that some patients have with their dialysis, and I came to learn about what other patients value from their cultural background,” he said.

With the photos now curated, the research team is returning to the question they posed at the beginning of the process: How can you take the resilience of some patients and share with others?

“You can’t bottle it and inject it during the next dialysis session, so we have to reflect on the successes achieved through the patient interaction during the phases of the project and take the feedback from our patients to share the photos to the broader community,” said Dr. McIntyre.

Part of that sharing included creating banners with the photos that can be displayed at special events and in the dialysis unit, presentations at research conferences, discussing the project part of an international meeting and creating a website to tell the story of the many aspects of the project.

Dr. Christopher McIntyre is Professor in the Departments of Medicine, Medical Biophysics and Paediatrics and the Robert Lindsay Chair of Dialysis Research and Innovation at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University. He also serves as Director of the Lilibeth Caberto Kidney Clinical Research Unit at London Health Sciences Centre, where he is also a practicing Clinical Nephrologist and is a scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute.

"Research: A study of resiliency" Written by Jennifer Parraga, BA'93

Director, Communications and Marketing, Schulich Medicine & Dentistry