While no government can call

a great artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for

the Federal Government to help create and sustain, not only a climate

encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and inquiry but also the material

conditions facilitating the release of creative talent.

[1]

-

The National Endowment for the Arts, Arts and Humanities Act of 1965.

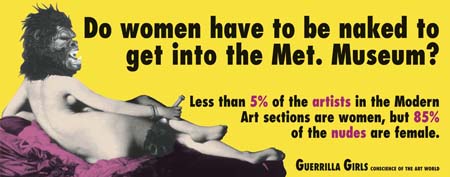

During the late 1980s

and early 1990s there were widespread debates in the American art world

regarding new and controversial subject matter in contemporary art. These

debates have become known as the Culture Wars. Conservative,

right-wing politicians and Christian fundamentalist groups adamantly attacked

the artistic representation of subject matter addressing gender, identity,

sexuality, AIDS and race, subjects that figured prominently in art production

at the time. American artists such as Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe

were under intense scrutiny by the aforementioned groups. Serrano, whose work

depicted themes of religious, racial and personal identity, provoked

controversy within the American Christian communities who labelled his photographs disgraceful, offensive and anti-Christian.

[2]

Similarly, Mapplethorpe’s photographs of explicit homoerotic activity mobilized

the mass attacks on contemporary art that characterized this particular

historical moment. During this

time, arguments based in a conservative or religious framework suggested that

artworks of overtly political or contentious nature had little to no

involvement with aesthetic beauty. However, how can a deliberate display of

politically challenging work generate artistic or intellectual meaning if

entirely void of aesthetically pleasing elements?

In order for artists

to become accessible, influential and powerful, they must work within the

construct of what is publicly and historically considered to be “art”. In this vein, artists have often

assumed an aesthetic position to produce works that are both visually

pleasing and aligned with artistic conventions. Alternatively, there are artists who assume an anti-aesthetic position in order to

create works that reflect social, political and historical criticism aimed at contemporaneity. Artists who embrace anti-aesthetics also question the viability of

concepts rooted in Enlightenment aesthetics and their direct parallel with

conservative taste.

[3]

Although

these two positions appear irreconcilable, artists like Serrano and

Mapplethorpe attempt to unify them within their work in order to amplify

intended meaning and true significance. According to them, aesthetic beauty is

the vehicle with which artists may reflect back upon society their own

embittered, outdated viewpoints. Beauty has allowed these artists to challenge conventional expectations

placed upon marginalized groups and artistic production as a whole. Unfortunately, while the unification of

these positions enabled Serrano and Mapplethorpe to successfully communicate

with a diverse audience, it also resulted in widespread viewer discomfort and

prompted drastic retaliation.

The relationship

between the American government and the art world was forever changed following

the 1980s and 1990s debates that hinged upon issues of decency in the arts.

During this time many offended individuals and groups waged a full-on attack

against contemporary art - including prominent religious figures like Reverend

Donald Wildmon (creator of the American Family

Association), right-wing politicians such as Republican Jesse Helms, and

various other Christian fundamentalist sects.

[4]

These influential figures branded the art of Andres Serrano and Robert

Mapplethorpe as anti-Christian, vulgar and indecent.

[5]

Consequently, these artists were thrust to the forefront of American media

culture where their subject matter underwent intense scrutiny and withstood

innumerable objections

[6]

. Serrano’s

photograph Piss

Christ (1987) was interpreted as a bigoted gesture against Christians,

and it ignited debates surrounding religion and its representation in the arts.

[7]

The cancellation of Mapplethorpe’s The Perfect Moment retrospective

exhibition in 1989 suggested that fear of severe funding cuts and public

retribution had successfully infiltrated the art world, and highlighted issues

of censorship and institutional responsibility.

[8]

During this time,

religious leaders and politicians ardently attacked America’s National

Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in an attempt to drastically reduce or eliminate

public funding for the arts. In 1989, Helms introduced an amendment that

directly challenged the NEA’s 1965 Arts and Humanities Act. It prohibited the

NEA from funding “obscene or indecent materials, including but not limited to

depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the exploitation of children, or individuals

engaged in sex acts; or materials which denigrate the objects or beliefs of the

adherents of a particular religion or non-religion.”

[9]

For quite some time thereafter, the visual arts were relentlessly criticized

and monetarily restricted with little to no defensive input from prominent art

institutions or the media.

Those on the

receiving end of inexorable scrutiny responded with unprecedented artistic

production governed by “perspectives so diverse as to defy categorization”

which perpetuated the ongoing, controversial dialogue between the state and art

institutions.

[10]

Following

drastic government funding reductions to the NEA, private foundations such as

Art Matters (1985) developed fellowships that were awarded to those

experimenting in the arts. Art Matters sought to promote art that examined

issues surrounding diversity, AIDS, censorship and funding. This foundation

also wished to explore the social and historical impact of the “cultural”

debate that came to define this influential, instructive moment.

[11]

Throughout the

twentieth century, artists and theorists have sought to determine whether or

not works of art can be both aesthetically beautiful (aesthetic) and politically challenging (anti-aesthetic). During this time, many artists positioned their

work in the subversive, anti-aesthetic context so as to comment on current

social and political issues; often employing

traditional aesthetics as a means of conveying them. For example, although the

Dadaists promoted anti-aesthetics in order to address the brutalities of World

War I, it has been argued that some of their work can be interpreted as

visually pleasurable nevertheless.

[12]

Artworks

that embody both aesthetic and anti-aesthetic qualities are not unique to this

particular time; in fact, they date back to the Romantic and Neo-Classical

periods with works such as Géricault’s The

Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819) and Delacroix’s Liberty Leading

the People(1830). These paintings are aesthetically pleasurable from a

modern perspective, yet still communicate poignant

political messages through disturbing, somewhat morbid imagery that was highly

contentious and controversial at the time of their production. Delacroix’s

painting honoured the strength and determination of

the French citizens following the Revolution in 1789, while Géricault’s statement of injustice and tragedy on the French ship Medusa was

considered a full-on political attack in 1819.

[13]

Similarly, Jacques-Louis David’s representation of a revolutionary martyr in The

Dead Marat(1793), with its intensely emotive, unnerving and barren

composition, is considered by some to be the greatest political image ever

painted.

[14]

Edouard Manet’s Execution

of Emperor Maximilian(1867), in its shameless display of military

barbarism, is said to have redefined the notion of Romantic sincerity to

“signify, not so much emotional integrity as artistic honesty.”

[15]

The aforementioned paintings are comparable to contemporary artworks that

address new and challenging subject matter while still working with traditional

media. These works, as well as those of Mapplethorpe and Serrano, are initially

granted an ontological status as “art” (“artistic honesty”) and are only later

challenged on the basis of their content whether or not traditional aesthetics

are employed (“emotional integrity”). The notions of artistic honesty over

emotional integrity in relation to the aesthetic and anti-aesthetic positions are very much at play in the

work of Serrano and Mapplethorpe, as well as within the context of the culture

wars. The artists’ personal proximity to and affinity with issues of gender,

sexuality, AIDS and identity paved the way for subsequent expressions of

artistic honesty.

The infiltration of

highly personalized, autobiographical content within the American art world

isolated artists of the late 1980’s and 1990’s; their aesthetic mastery and

artistic execution were discounted by those incapable of seeing past the

unconventional intimacy of their content. In contemporary society, it is not

uncommon for one person to advocate for an entire marginalized community. This “artistic martyr” becomes

synonymous with changes in the art world, government and society. Although the

works of said artists did portray an acute attention to formal qualities and

classical composition, their subject matter furiously attacked artistic

conventions. Consequently, the

rise of identity politics during the culture wars came to define the crucial

and continuing connection between art and history. Despite perpetual criticism

in this regard, both Mapplethorpe and Serrano helped to advance the

ever-changing, ever-progressive vision that defines the history of art.

The highly contentious

nature of Serrano’s work is due to its religious and morbid content. Using

photography as a medium for self-reflection, Serrano explores issues pertaining

to his own religious upbringing as well as those of illness, identity,

immortality and death. The content of particular photographs can be disturbing,

unnerving and at times nauseating. At first glance, Serrano’s Bloodstream (1987) and Bloodscape IX (1989) are two photographs that appear inoffensive and harmless in that they

closely resemble expertly rendered abstract paintings.

[16]

However, many people were appalled

after the artist revealed that the deep, immersive reds and elegant whites were

in fact blood and semen. Serrano justified his incorporation of abnormal media

through a juxtaposition of positive and negative connotations. He highlighted

the redeeming and revitalizing qualities of blood and semen in order to

counteract their impure, deadly associations with homosexuality and AIDS.

[17]

Serrano’s ability to encourage meditation upon the beauty and luxury of his

unconventional subject matter articulates the profundity of his practice.

Serrano invites the

audience to contemplate their own spirituality in his religious photography. He

encouraged his viewers to look beyond socially constructed identity in the Nomads or Klansman series (1990), and to meditate upon issues of life and death in The

Morgue photographs (1992).

[18]

His most

controversial photographs to date are those that explored bodily fluids and how

they relate to personal identity. Piss Christ (1987), a photograph that

depicts a small crucifix submerged in the artist’s urine, came to exemplify

what religious officials and conservative politicians perceived as everything

wrong in the contemporary art world. Consequently, this image prompted much debate

over whether or not American tax dollars should fund such unorthodoxy.

[19]

Senator Jesse Helms labelled the photograph “o as bscene” and

“indecent,” and used his 1989 amendment to prohibit artistic expression of

themes that relate to or challenge religion and political or personal identity.

[20]

Due to the blasphemous

and offensive nature of Piss Christ, it was seen by many as nothing more than a blatant

display of anti-Christian discrimination. According to Serrano this work

embodied a “rejection of organized attempts to co-opt religion in the name of

Christ,” for at the time there was no way to mend the gap between art world

concerns and those who contested them.

[21]

An examination of Serrano’s work

reveals that the artist used formal qualities such as colour,

light and composition to convey underlying meanings beyond the immediate

surface. For example, in Piss Christ, the use of a brightly lit

background enhanced the photograph’s lustrous glow, while evoking religious

inspiration through an artistic display of divine serenity. Through formally

brilliant photography, Serrano equates relevant artistic concerns with

prominent contemporary issues while offering his viewers a new perspective on

approaching and interpreting art.

Serrano takes an

idiosyncratic, avant-garde approach in order to institute social, political and

artistic change. Prominent art world critic Arthur Danto feels that “every new

work of creative design is ugly until it is beautiful”; in other words, the

avant-garde is initially considered an abomination until its meaning is

recognized as necessary for progression in the arts and society at large.

[22]

Artworks are often labeled offensive or antagonistic when the artist’s medium

is interpreted as one that contradicts his or her message. In fact, many are

unable to accept the visual manifestation of a concept when they perceive it as

distasteful. Serrano uses oppositional imagery in order to unify viewpoints

previously considered irreconcilable. His work, which could be understood as

the single catalyst for the culture wars as a whole, questions traditionally

ethical content and effectively upsets American bourgeois complacency.

The opposition and

ultimate unification of medium and message in Serrano’s photographs undermines

the seemingly irreconcilable positions of the aesthetic and anti-aesthetic.

Serrano’s descriptive titles employ anti-aesthetic tactics that allow his

viewers to embrace or reject his art. For example, as in Piss Christ, the artist alerted the viewer to his use of bodily

fluids. This work, amongst many others by Serrano, uses unconventional media to

echo the colouration of formal painting or the tonal

range of contemporary photography, which refuses to meet conservative

expectations and challenges dogmatic definitions of “art”. Piss Christ’s grand scale and portrayal of a luminescent Jesus

Christ reflects the artist’s mastery of formal characteristics such as value, colour and composition. Although Serrano consistently

adheres to these traditional aesthetics, he also uses what James Meyer and Toni

Ross call an “avant-garde strategy of estrangement” to emphasize his own

inquisitions regarding religious identity and personal heritage.

[23]

This has allowed him to illustrate and address previously unmentionable

subjects through visually pleasurable displays of complex issues, thus

perpetuating the progressivism that defines contemporary art.

[24]

Robert Mapplethorpe’s

photographs are similar to Serrano’s in that they are technically and formally

very strong. His photographs encompassed both traditional subjects, such as

still-lifes, nudes, portraits and children, as well

as non-traditional subjects, such as his blatant depictions of homoeroticism. Although

his portraits of children and nudes garnered much controversy, it was the

physical sensuality of his homoerotic photographs that were labeled “extreme”

by politicians and religious officials.

[25]

The controversial nature of these photographs prompted the Corcoran Gallery in

Washington, D.C. to cancel Mapplethorpe’s posthumous retrospective, The

Perfect Moment, in 1989. The gallery was paralyzed by the prevalent fear of

future funding cuts as Mapplethorpe’s work exemplified everything that was

perceived as morally corrupt within the American art world.

[26]

The cancellation of this exhibition illustrated the collective power of the

religious or offended communities who sought to literally eliminate freedom of

artistic expression. Although the exhibition was eventually rescheduled and

held at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Pennsylvania that same year, it

would ultimately characterize the debates surrounding his work that arose

thereafter.

[27]

Mapplethorpe’s

photographic practice exemplified his ability to frame highly controversial

subject matter in an aesthetically pleasing manner. However, the social and

political objection to his errant depictions of human sexuality cannot easily

be settled through the simple justification of artistic execution. Many people

were unable to comprehend the gravity of Mapplethorpe’s work, and the lack of

support from prominent figures in the art world only contributed to this

confusion. Institutional representatives were reluctant to defend his work for

they were concerned that this would result in significant funding cuts. This tendency to shy away from further

controversy validated the arguments made by the right-wing and religious communities.

[28]

Art world

experts simply discussed Mapplethorpe’s work in terms of its formal qualities

and technical perfection, as though absolving its shocking subject matter.

[29]

In order to properly understand and accept Mapplethorpe’s work, one must look

beyond what is immediately visible to the much larger issues that inform his

imagery. Ultimately, politically challenging artwork, specifically that which

adamantly attacks upheld conventions, must be examined within its own

contemporary, artistic context.

The shameless

exhibitionism that characterizes Mapplethorpe’s subject matter allowed the

artist to communicate with a diverse audience while upsetting traditional

conventions of portraiture. While Serrano’s work speaks to many different

communities, Mapplethorpe’s generally addressed the marginalized male

homosexual population. According

to scholar Brian Wallis, religious and conservative revulsion in response to

works such as Helmut (1978) or Joe (1978) is inevitable because it is difficult to explain, let alone accept art

that so blatantly attacks established moral values.

[30]

Similarly, although Mapplethorpe was working in the guise of aesthetic

pleasure, he photographed many taboo issues that offended deeply conservative

and/or religious individuals. For example, in Marty and Hank (1982)

Mapplethorpe overtly depicted two men engaged in oral sex. The artist’s

brilliant manipulation of formal qualities in this work contains a symbolic

meaning beneath its surface.

[31]

The

photograph’s subject matter, as articulated by Philip Yenawine,

proclaims that a homosexual man has just as much right to a “public

presentation of autobiography as anyone else.”

[32]

All the same, Mapplethorpe struggled with imposed and engrained artistic

conventions in order to merge the beautiful with the political. A display of

such unmediated, unconventional imagery will perhaps remain invariably

contentious, establishing polarized views and arguments. Nevertheless,

Mapplethorpe’s imagery confirms his accomplishment in merging the aesthetic and

anti-aesthetic positions.

Mapplethorpe existed as

much on the margins of society as he did at the centre of the art world. He

struggled to define himself as a homosexual man living with AIDS during a time

when many Americans were openly homophobic. The politically charged nature of

his work is in response to that which is ignored in society and rarely

addressed in contemporary art. Mapplethorpe used aesthetic beauty in order to

investigate and validate the unexamined themes that defined his life and

artistic practice.

[33]

He

successfully employed conventional aesthetics to convey unconventional messages

that enabled him to define his own unique, artistic approach.

No matter where one

stands in relation to these culture wars, it is important to recognize that Mapplethorpe’s

artwork is a metaphor for the life of a man, of an advocate, who strove for

recognition and equality on behalf of a marginalized community. As explained by Henry M. Sayre, his

work is not about sadomasochistic sexual behaviour,

it is about “cutting through the surface of things and bringing them to light,

which is to say, is about making art.”

[34]

Within the context of the culture wars, the surface of things dictated

convention and control. Mapplethorpe’s art helped to dispose of these surface

expectations to reveal that which exists below: the governing forces of his own

life and those of many others. Art constantly disfigures reality. Thus, an

abolition of established convention can refigure public consciousness to

instigate social, political and creative progress, even if through

illustrations of past aesthetic principles.

[35]

Both Andres Serrano and

Robert Mapplethorpe effectively merged the aesthetic and anti-aesthetic

positions in their artwork. Although in very different ways and necessitating different

justification, each artist challenged convention and contributed to the visual

arts’ inevitable progression. Serrano and Mapplethorpe’s aesthetically pleasing

photographs commented on social and political issues that were important to

Americans during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The fusion of aesthetic beauty

and politically challenging content defined the artistic practice of many

during this period. Their mandate to oppose artistic conventions through

formally precise, visually pleasurable aesthetics continues to re-define

message, power and influence in contemporary art today. Whether one supports

the radically arrière-garde position of the

right-wing conservatives or the avant-garde position of the art world, it is

imperative to recognize the importance of the culture wars. These struggles

shaped future direction in the arts, aroused new debates while settling others,

and characterized subsequent movements that have impacted contemporary artistic

production indefinitely.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bolton, Richard. Culture Wars: Documents

from the Recent Controversies in the Arts. New York: New Press, 1992.

Danto, Arthur C. “Kalliphobia in Contemporary Art.” Art Journal, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 24-35.

Furgurson, Ernest B. Hard Right:

The Rise of Jesse Helms. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1986.

Honour, Hugh and

Fleming, John. The Visual Arts: A History. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2005.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Ten

By Ten. Berlin: Schirmer/Mosel, 1988.

Meyer, James and Ross, Toni. “Aesthetic and

Anti-Aesthetic: An Introduction.” Art Journal, no.2 (2004): 20-23.

Nolan Jr., James L. The American Culture

Wars: Current Contests and Future Prospects. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

Sayre, Henry M. “Scars: Painting,

Photography, Performance, Pornography and the Disfigurement of Art.” Performing

Arts Journal, no. 1 (1994): 64-74.

Wallis, Brian. Andres Serrano: Body and

Soul. New York: Takarajima Books, 1995.

Wallis, Brian. Art Matters: How the

Culture Wars Changed America. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

NOTES