| |

Yves

Klein's Monopinks:

An Account of My Impregnation

by Colour - Sarah Kyle

Yves Klein first began the exploration of alternate monochromes around

1959 with a series of Monogolds and Monopinks. Up until this time, Klein's

focus was undeniably the International Klein Blue that marks majority of

his work. This branching out of the new monochromes beyond the blue, or

as he would argue, further into the blue, establishes a pattern of trinity

within Klein's art; arguably, this trinity, of Žcrimson/rose', gold, and

blue, continues Mondrian's commentary on the triad of primary colours as

the material representation of the "cosmic philosophy about harmony and

order" (Stich 194). While Klein denied Mondrian's influence, and,

in effect created a message of a cosmic order of faith, Mondrian's work

acts as a complement to, and perhaps foundation for, Klein's monochromes

(Stich 194). Another potential influence of Klein's exploration of colour-field

is Rauschenberg's ŽGold Painting' of 1953, which sought to comment on the

physicality of the earth's element gold. Conversely, Klein's work represents

the symbolic opposite: for Klein, gold, in combination with the blue and

pink, marks a conduit between the temporal, material world and the immaterial

world (Stich 194). Klein's monopinks come to represent, then, alongside

the transcendent blue and the infinite, immaterial gold, the third aspect

of a trinity that reaches beyond Mondrian's triad of primary colours. The

pinks symbolize the virtue of caritas. This virtue encompasses charity

expressed through love, and is known in the Christian vocabulary as the

Holy Spirit. This paper will explore the Klein's monopinks as the material

representation of divine Love in a trinity of colour, whereby blue and

gold represent, respectively, the ineffable infinite (God as Faith), and

the eternal hope and harmony (God as Hope).

Yves Klein first began the exploration of alternate monochromes around

1959 with a series of Monogolds and Monopinks. Up until this time, Klein's

focus was undeniably the International Klein Blue that marks majority of

his work. This branching out of the new monochromes beyond the blue, or

as he would argue, further into the blue, establishes a pattern of trinity

within Klein's art; arguably, this trinity, of Žcrimson/rose', gold, and

blue, continues Mondrian's commentary on the triad of primary colours as

the material representation of the "cosmic philosophy about harmony and

order" (Stich 194). While Klein denied Mondrian's influence, and,

in effect created a message of a cosmic order of faith, Mondrian's work

acts as a complement to, and perhaps foundation for, Klein's monochromes

(Stich 194). Another potential influence of Klein's exploration of colour-field

is Rauschenberg's ŽGold Painting' of 1953, which sought to comment on the

physicality of the earth's element gold. Conversely, Klein's work represents

the symbolic opposite: for Klein, gold, in combination with the blue and

pink, marks a conduit between the temporal, material world and the immaterial

world (Stich 194). Klein's monopinks come to represent, then, alongside

the transcendent blue and the infinite, immaterial gold, the third aspect

of a trinity that reaches beyond Mondrian's triad of primary colours. The

pinks symbolize the virtue of caritas. This virtue encompasses charity

expressed through love, and is known in the Christian vocabulary as the

Holy Spirit. This paper will explore the Klein's monopinks as the material

representation of divine Love in a trinity of colour, whereby blue and

gold represent, respectively, the ineffable infinite (God as Faith), and

the eternal hope and harmony (God as Hope).

The noble pursuit

of the Rosicrucian Order contextualizes Klein's fascination with a Trinity,

or a union of Many as One. Klein began his formal initiation into the Order

of the Rose and Cross in 1947, a year after he read the ŽCosmogony of the

Rose Cross', the essential manual of Rosicrucianism (McEvilley 239). Until

1958 Klein remained an active member of the Oceanside, California school

of Rosicrucianism via correspondence. By 1958 his membership and Žhomework'

lapsed, however, the traditions of union, transcendence, and the betterment

of humanity, that the Order espoused, continued to dominated Klein's philosophy

and manifest itself in his art (McEvilley 239). The central goal of the

Rosicrucian tradition is the "ultimate synthesis of life and form" (McEvilley

240). ŽLife' is defined as "pure spirit", and 'form' as physical

matter. According to this ideology, the two have been completely

divorced from one anther (McEvilley 240). Thus, for Klein, as for

the Rosicrucians, the purpose of existence on earth was to strive for the

reunion of Life and Form, or, to aspire to godliness despite the constraints

of the humanity. This philosophy is deeply Neo-Platonic, and a close relation

to the Tree of Life of the Christian Kabbalah.

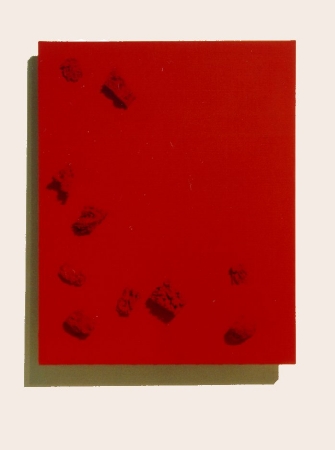

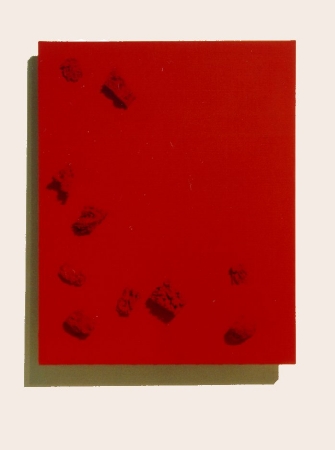

Klein's Ex Voto box left at Saint Rita's shrine, in Cascia, Italy, is a

testament to this Rosicrucian vision that encompasses both the Christian

Trinity and, what the Rosicrucians term, the Trinity of Fire. The Trinity

of Fire is ostensibly the three theological virtues of Christianity (Faith,

Hope, and Charity), which are both implied and inherent in the three parts

of the Christian Godhead. Blue, Gold, and Pink, then, come to symbolically

represent Faith, Hope, and Charity, which together form the ineffable union

for which Klein's work aims. The Monopinks epitomize the third virtue of

godliness: Love. What better colour to choose to express the benevolence

of godly charity than crimson, or rose? Its brilliance refuses to be denied

and, as intended, invades and permeates the viewers' space without the

violence associated with red. The viewer is enveloped in the colour-manifestation

of divine grace. Now, granted, Klein's self-proclaimed prophet-status,

carrying the grace of the divine to his viewer, is clearly a presumptuous

one. Despite Klein's rampant megalomania, the wonder he infused in his

life, and actualized in his art, transcends his ego. He desired to communicate

a joyous vision, one that he believed, as a dutiful Rosicrucian, would

better humankind. This is evident in his prayer to Saint Rita enclosed

in the votive box: he states "grant me thy aid still and always in my art

and always protect all I have created so that even in spite of myself it

may always be of Great Beauty" (Klein 257). Despite the clearly elf-important

bent of his prayer, Klein requests divine aid in conveying beauty, as a

manifestation of God's grace, to a jaded public. In an age of fragmentation

and post-war pessimism marked by the nihilism of the existential philosophers,

Klein's reinstatement of the Trinitarian virtues, and the unity that they

represent, endeavours to dispel the negativity and stasis of post-World

War II Europe. For Klein the Immaterial, that he sought to represent via

his Monochromes and the exhibition of the Void, provides a synthesis of

our material reality with the divine (Restany 14). In this light, Klein's

monochromes mark his attempt to ratify Life and Form. As Pierre Restany

states in his article "Who is Yves Klein?",

Klein's Ex Voto box left at Saint Rita's shrine, in Cascia, Italy, is a

testament to this Rosicrucian vision that encompasses both the Christian

Trinity and, what the Rosicrucians term, the Trinity of Fire. The Trinity

of Fire is ostensibly the three theological virtues of Christianity (Faith,

Hope, and Charity), which are both implied and inherent in the three parts

of the Christian Godhead. Blue, Gold, and Pink, then, come to symbolically

represent Faith, Hope, and Charity, which together form the ineffable union

for which Klein's work aims. The Monopinks epitomize the third virtue of

godliness: Love. What better colour to choose to express the benevolence

of godly charity than crimson, or rose? Its brilliance refuses to be denied

and, as intended, invades and permeates the viewers' space without the

violence associated with red. The viewer is enveloped in the colour-manifestation

of divine grace. Now, granted, Klein's self-proclaimed prophet-status,

carrying the grace of the divine to his viewer, is clearly a presumptuous

one. Despite Klein's rampant megalomania, the wonder he infused in his

life, and actualized in his art, transcends his ego. He desired to communicate

a joyous vision, one that he believed, as a dutiful Rosicrucian, would

better humankind. This is evident in his prayer to Saint Rita enclosed

in the votive box: he states "grant me thy aid still and always in my art

and always protect all I have created so that even in spite of myself it

may always be of Great Beauty" (Klein 257). Despite the clearly elf-important

bent of his prayer, Klein requests divine aid in conveying beauty, as a

manifestation of God's grace, to a jaded public. In an age of fragmentation

and post-war pessimism marked by the nihilism of the existential philosophers,

Klein's reinstatement of the Trinitarian virtues, and the unity that they

represent, endeavours to dispel the negativity and stasis of post-World

War II Europe. For Klein the Immaterial, that he sought to represent via

his Monochromes and the exhibition of the Void, provides a synthesis of

our material reality with the divine (Restany 14). In this light, Klein's

monochromes mark his attempt to ratify Life and Form. As Pierre Restany

states in his article "Who is Yves Klein?",

[The monochromes]

were never intended . . . to be decorative Žpictures'. Their function was

entirely different: they were meant to gather the diffused energy that

acts on our sense and to fix it, by means of colour, in a certain space.

(15)

What Restany proposes is that

Klein's monochromes sought to focus the viewer's attention through their

intensity and completeness, upon the ineffable and the transcendent unity

beyond our material existence. Klein's philosophy expressed through

the Monochromes is the antithesis (and perhaps response) to the completely

secular focus of the existentialists.

Notably, Klein's ideology of synthesis did spiral into naïve irrationality,

for which he was labelled both a charlatan and a fraud (Rosenthal 129):

Klein hoped that in the future people would be able to complete the transcendence

of body while still alive. He hoped that people could eventually

escape the materiality of the world, and its inherent limitations, via

levitation, out-of-body experiences, and telepathy. Klein thought that

this subversion of the physical was the key to a new Eden, and that it

heralded the "union of science, art and religion" (McEvilley 241).

Restany states, "Klein acted as a prophet, but in the service of the Order

of God" (15). Klein certainly fashioned himself as a prophet. In reality,

he was more of a naïve visionary. However, in an age bent upon Line,

divisions, and the negative anxiety that accompanies them, Klein's work

carries a message of Hope for unity beyond the pessimism, death, and destruction

that the world had so recently witnessed. Klein's philosophy on art revolved

around eliminating lines and the boundaries that contain and segregate

humanity. He believed that "line divides and obstructs the pure space of

cosmic sensibility, while colour asserts the freedom and fullness of space"

(McEvilley 239). In this light, Klein's monopinks symbolize the cosmic

embrace, the love inherent in hope and faith, and the freedom that this

hopefulness enables.

Notably, Klein's ideology of synthesis did spiral into naïve irrationality,

for which he was labelled both a charlatan and a fraud (Rosenthal 129):

Klein hoped that in the future people would be able to complete the transcendence

of body while still alive. He hoped that people could eventually

escape the materiality of the world, and its inherent limitations, via

levitation, out-of-body experiences, and telepathy. Klein thought that

this subversion of the physical was the key to a new Eden, and that it

heralded the "union of science, art and religion" (McEvilley 241).

Restany states, "Klein acted as a prophet, but in the service of the Order

of God" (15). Klein certainly fashioned himself as a prophet. In reality,

he was more of a naïve visionary. However, in an age bent upon Line,

divisions, and the negative anxiety that accompanies them, Klein's work

carries a message of Hope for unity beyond the pessimism, death, and destruction

that the world had so recently witnessed. Klein's philosophy on art revolved

around eliminating lines and the boundaries that contain and segregate

humanity. He believed that "line divides and obstructs the pure space of

cosmic sensibility, while colour asserts the freedom and fullness of space"

(McEvilley 239). In this light, Klein's monopinks symbolize the cosmic

embrace, the love inherent in hope and faith, and the freedom that this

hopefulness enables.

Klein, of course, chose

his distinctive ultra-marine blue as the pinnacle of the transcendence

and harmony to which he aspired. He describes the blue in terms of revelation,

infinity, and union beyond all worlds (Restany 15). However, this does

not discount the importance of the other monochromes. For, when joined

with the Monogolds and Monopinks Klein's trinity of colour represents a

reflection on the divine union, the three in one of the godhead. This impulse

towards unification in his art ultimately provided the impetus for Klein

to incorporate the elements of nature and the human body into his work

(Restany 15).

Part

II: Interplay Part

II: Interplay

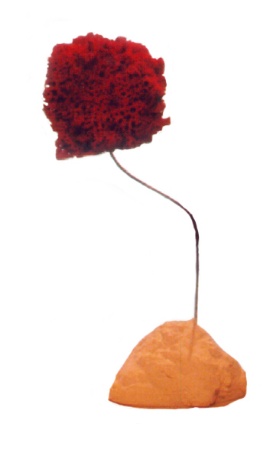

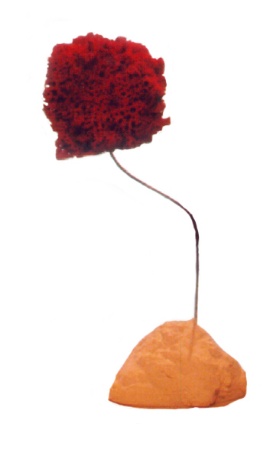

As far as my

interaction with Klein's work in the re-creation of the Monopinks and the

pink sponges, I have a small anecdote to relate. My background in art is

one deeply entrenched in the structure and ideal aestheticism surrounding

the Italian Renaissance. Thus, I approached Klein's work with a heavy dose

of scepticism and resistance. Quite naturally, I was wary of the process

of re-creating Klein's visions on canvas. However, in pondering Klein's

goal, of actualizing a representation of the ineffable in order to infuse

humanity with hope again, I thought I would put aside my reservations and

give Klein the benefit of the doubt.

As I was dutifully

painting sponges, and becoming more and more frustrated with the colourless

gaps in their centres, John (Klein's messenger, to be sure) said to me

Žengage with it, Sarah. Pick it up in your hands and work with the paint'.

Whether John was just tired of watching my fumbled attempts, or whether

he truly sought to enlighten me, I was struck with an epiphany. For the

first time since my childhood, I became joyfully messy, and I let paint

get under my fingernails. Ostensibly, my interaction with Klein's message

and media realized the joyous hope and associated with Klein's philosophy.

It occurred to me that by physically interacting with the medium within

the context of representing transcendent Love, an intriguing dialectic

between the secular and the sacred is established. This interplay between

the physicality of Klein's art, and the invasion of the senses by brilliant

colour, becomes the part of the ascent to participating in the divine.

The physical experience of re-visioning Klein's work converted me to his

utopian ideology (at least temporarily); in his art I see an euphoric,

though naively simplistic, prayer for unity through hope and love, of which

our world is in dire need.

Bibliography

Arman. "Selected quotes."

In Arman: 1955-1991 A Retrospective. (Alison

de Lima Greene, Pierre Restany.)

Exh. Cat. Houston, Brooklyn,

Detroit. Houston: The Museum

of Fine Arts, 1992. 88.

Bozo, Dominique. "Yves Klein:

Arrogance and Angelism." In Yves Klein:

1928-1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New York,

Paris. Houston: Institute

for the Arts, 1982. 11.

Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. "Into

the Blue: Klein and Poses," Artforum. Vol. 33,

Summer 1995. 92-97, 130,

136.

De Duve, Thierry. "Yves

Klein, or The Dead Dealer," October. No. 49,

Summer 1989. 77-90.

Klein, Yves. "Prayer to Saint

Rita." In Yves Klein: 1928-1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago,

New York, Paris. Houston: Institute for

the Arts, 1982. 257.

_________. "Selections

from The Monochrome Adventure." In Yves Klein:

1928-1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New York,

Paris. Houston: Institute

for the Arts, 1982. 220-224.

_________. "Selections

from The War: A Little Personal Mythology of the

Monochrome." In Yves

Klein: 1928-1962 A Retrospective. Exh. Cat.

Houston, Chicago, New York,

Paris. Houston: Institute for the Arts,

1982. 218-220.

McEvilley, Thomas.

"Yves Klein and Rosicrucianism." In Yves Klein: 1928-

1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New York, Paris.

Houston: Institute for the

Arts, 1982. 238-255.

Mock, Jean-Yves. "Yves

Klein: An Appreciation." In Yves Klein: 1928-1962

A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New York, Paris.

Houston: Institute for the

Arts, 1982. 12.

Restany, Pierre. "Yves

Klein: The Ex-Voto for Saint Rita of Cascia." In Yves

Klein: 1928-1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New

York, Paris. Houston: Institute

for the Arts, 1982. 255-257.

Rosenthal, Nan. "Assisted

Levitation: The Art of Yves Klein." In Yves Klein:

1928-1962 A Retrospective.

Exh. Cat. Houston, Chicago, New York,

Paris. Houston: Institute

for the Arts, 1982. 89-135.

_________. "Into the

Blue: Comic Relief," Artforum. Vol. 33, Summer

1995. 92-97, 130, 136.

Stich, Sidra. Yves Klein.

Exh. Cat. Stuttgart and London: Cantz Verlag and

the Hayward Gallery, 1994.

http://www.crcsite.org

Conversely,

Thierry De Duve argues that Klein's philosophy and art were wholly self-absorbed.

He states that Klein's art does not promote hope, and, is instead enslaved

to consumerism and the maintenance of capitalism's reign. The virtually

zero-profit of Klein's work, however, attests to a value beyond the all-mighty

franc.

Incidentally, Arman's

philosophy and art of destruction, segregation, deconstruction, and isolation

of objects represents the opposite of Klein's holism: these two artists

juxtapose of The Full, as representative of the emptiness of society, with

the Void, as representative of the full, infinite potential of the divine

both in and beyond humanity. Arman and Klein had "divided the world . .

. [Klein] had said to [Arman] ŽI will concern myself with what is organic,

and you will take what is manufactured'" (Arman 88). The art of Arman

and Klein, respectively, explores Form, as the objective reality that separates

humanity from God, and Life, which eliminates the object and unifies humanity

with God.

The entire canon

of Neo-Platonic thought hinges upon the impossibility of this occurrence:

for if one could transcend the body while still inhabiting it, one would

transcend humanity and, thus, be a god. The nature of the Neo-Platonic

faith necessitates the struggle toward proximity to godliness. For it is

by way of this struggle that the practitioner learns the nature of virtuous

humanity and can, thus, better emulate and appreciate god.

|

|

Yves Klein first began the exploration of alternate monochromes around

1959 with a series of Monogolds and Monopinks. Up until this time, Klein's

focus was undeniably the International Klein Blue that marks majority of

his work. This branching out of the new monochromes beyond the blue, or

as he would argue, further into the blue, establishes a pattern of trinity

within Klein's art; arguably, this trinity, of Žcrimson/rose', gold, and

blue, continues Mondrian's commentary on the triad of primary colours as

the material representation of the "cosmic philosophy about harmony and

order" (Stich 194). While Klein denied Mondrian's influence, and,

in effect created a message of a cosmic order of faith, Mondrian's work

acts as a complement to, and perhaps foundation for, Klein's monochromes

(Stich 194). Another potential influence of Klein's exploration of colour-field

is Rauschenberg's ŽGold Painting' of 1953, which sought to comment on the

physicality of the earth's element gold. Conversely, Klein's work represents

the symbolic opposite: for Klein, gold, in combination with the blue and

pink, marks a conduit between the temporal, material world and the immaterial

world (Stich 194). Klein's monopinks come to represent, then, alongside

the transcendent blue and the infinite, immaterial gold, the third aspect

of a trinity that reaches beyond Mondrian's triad of primary colours. The

pinks symbolize the virtue of caritas. This virtue encompasses charity

expressed through love, and is known in the Christian vocabulary as the

Holy Spirit. This paper will explore the Klein's monopinks as the material

representation of divine Love in a trinity of colour, whereby blue and

gold represent, respectively, the ineffable infinite (God as Faith), and

the eternal hope and harmony (God as Hope).

Yves Klein first began the exploration of alternate monochromes around

1959 with a series of Monogolds and Monopinks. Up until this time, Klein's

focus was undeniably the International Klein Blue that marks majority of

his work. This branching out of the new monochromes beyond the blue, or

as he would argue, further into the blue, establishes a pattern of trinity

within Klein's art; arguably, this trinity, of Žcrimson/rose', gold, and

blue, continues Mondrian's commentary on the triad of primary colours as

the material representation of the "cosmic philosophy about harmony and

order" (Stich 194). While Klein denied Mondrian's influence, and,

in effect created a message of a cosmic order of faith, Mondrian's work

acts as a complement to, and perhaps foundation for, Klein's monochromes

(Stich 194). Another potential influence of Klein's exploration of colour-field

is Rauschenberg's ŽGold Painting' of 1953, which sought to comment on the

physicality of the earth's element gold. Conversely, Klein's work represents

the symbolic opposite: for Klein, gold, in combination with the blue and

pink, marks a conduit between the temporal, material world and the immaterial

world (Stich 194). Klein's monopinks come to represent, then, alongside

the transcendent blue and the infinite, immaterial gold, the third aspect

of a trinity that reaches beyond Mondrian's triad of primary colours. The

pinks symbolize the virtue of caritas. This virtue encompasses charity

expressed through love, and is known in the Christian vocabulary as the

Holy Spirit. This paper will explore the Klein's monopinks as the material

representation of divine Love in a trinity of colour, whereby blue and

gold represent, respectively, the ineffable infinite (God as Faith), and

the eternal hope and harmony (God as Hope).

Klein's Ex Voto box left at Saint Rita's shrine, in Cascia, Italy, is a

testament to this Rosicrucian vision that encompasses both the Christian

Trinity and, what the Rosicrucians term, the Trinity of Fire. The Trinity

of Fire is ostensibly the three theological virtues of Christianity (Faith,

Hope, and Charity), which are both implied and inherent in the three parts

of the Christian Godhead. Blue, Gold, and Pink, then, come to symbolically

represent Faith, Hope, and Charity, which together form the ineffable union

for which Klein's work aims. The Monopinks epitomize the third virtue of

godliness: Love. What better colour to choose to express the benevolence

of godly charity than crimson, or rose? Its brilliance refuses to be denied

and, as intended, invades and permeates the viewers' space without the

violence associated with red. The viewer is enveloped in the colour-manifestation

of divine grace. Now, granted, Klein's self-proclaimed prophet-status,

carrying the grace of the divine to his viewer, is clearly a presumptuous

one. Despite Klein's rampant megalomania, the wonder he infused in his

life, and actualized in his art, transcends his ego. He desired to communicate

a joyous vision, one that he believed, as a dutiful Rosicrucian, would

better humankind. This is evident in his prayer to Saint Rita enclosed

in the votive box: he states "grant me thy aid still and always in my art

and always protect all I have created so that even in spite of myself it

may always be of Great Beauty" (Klein 257). Despite the clearly elf-important

bent of his prayer, Klein requests divine aid in conveying beauty, as a

manifestation of God's grace, to a jaded public. In an age of fragmentation

and post-war pessimism marked by the nihilism of the existential philosophers,

Klein's reinstatement of the Trinitarian virtues, and the unity that they

represent, endeavours to dispel the negativity and stasis of post-World

War II Europe. For Klein the Immaterial, that he sought to represent via

his Monochromes and the exhibition of the Void, provides a synthesis of

our material reality with the divine (Restany 14). In this light, Klein's

monochromes mark his attempt to ratify Life and Form. As Pierre Restany

states in his article "Who is Yves Klein?",

Klein's Ex Voto box left at Saint Rita's shrine, in Cascia, Italy, is a

testament to this Rosicrucian vision that encompasses both the Christian

Trinity and, what the Rosicrucians term, the Trinity of Fire. The Trinity

of Fire is ostensibly the three theological virtues of Christianity (Faith,

Hope, and Charity), which are both implied and inherent in the three parts

of the Christian Godhead. Blue, Gold, and Pink, then, come to symbolically

represent Faith, Hope, and Charity, which together form the ineffable union

for which Klein's work aims. The Monopinks epitomize the third virtue of

godliness: Love. What better colour to choose to express the benevolence

of godly charity than crimson, or rose? Its brilliance refuses to be denied

and, as intended, invades and permeates the viewers' space without the

violence associated with red. The viewer is enveloped in the colour-manifestation

of divine grace. Now, granted, Klein's self-proclaimed prophet-status,

carrying the grace of the divine to his viewer, is clearly a presumptuous

one. Despite Klein's rampant megalomania, the wonder he infused in his

life, and actualized in his art, transcends his ego. He desired to communicate

a joyous vision, one that he believed, as a dutiful Rosicrucian, would

better humankind. This is evident in his prayer to Saint Rita enclosed

in the votive box: he states "grant me thy aid still and always in my art

and always protect all I have created so that even in spite of myself it

may always be of Great Beauty" (Klein 257). Despite the clearly elf-important

bent of his prayer, Klein requests divine aid in conveying beauty, as a

manifestation of God's grace, to a jaded public. In an age of fragmentation

and post-war pessimism marked by the nihilism of the existential philosophers,

Klein's reinstatement of the Trinitarian virtues, and the unity that they

represent, endeavours to dispel the negativity and stasis of post-World

War II Europe. For Klein the Immaterial, that he sought to represent via

his Monochromes and the exhibition of the Void, provides a synthesis of

our material reality with the divine (Restany 14). In this light, Klein's

monochromes mark his attempt to ratify Life and Form. As Pierre Restany

states in his article "Who is Yves Klein?",

Notably, Klein's ideology of synthesis did spiral into naïve irrationality,

for which he was labelled both a charlatan and a fraud (Rosenthal 129):

Klein hoped that in the future people would be able to complete the transcendence

of body while still alive. He hoped that people could eventually

escape the materiality of the world, and its inherent limitations, via

levitation, out-of-body experiences, and telepathy. Klein thought that

this subversion of the physical was the key to a new Eden, and that it

heralded the "union of science, art and religion" (McEvilley 241).

Restany states, "Klein acted as a prophet, but in the service of the Order

of God" (15). Klein certainly fashioned himself as a prophet. In reality,

he was more of a naïve visionary. However, in an age bent upon Line,

divisions, and the negative anxiety that accompanies them, Klein's work

carries a message of Hope for unity beyond the pessimism, death, and destruction

that the world had so recently witnessed. Klein's philosophy on art revolved

around eliminating lines and the boundaries that contain and segregate

humanity. He believed that "line divides and obstructs the pure space of

cosmic sensibility, while colour asserts the freedom and fullness of space"

(McEvilley 239). In this light, Klein's monopinks symbolize the cosmic

embrace, the love inherent in hope and faith, and the freedom that this

hopefulness enables.

Notably, Klein's ideology of synthesis did spiral into naïve irrationality,

for which he was labelled both a charlatan and a fraud (Rosenthal 129):

Klein hoped that in the future people would be able to complete the transcendence

of body while still alive. He hoped that people could eventually

escape the materiality of the world, and its inherent limitations, via

levitation, out-of-body experiences, and telepathy. Klein thought that

this subversion of the physical was the key to a new Eden, and that it

heralded the "union of science, art and religion" (McEvilley 241).

Restany states, "Klein acted as a prophet, but in the service of the Order

of God" (15). Klein certainly fashioned himself as a prophet. In reality,

he was more of a naïve visionary. However, in an age bent upon Line,

divisions, and the negative anxiety that accompanies them, Klein's work

carries a message of Hope for unity beyond the pessimism, death, and destruction

that the world had so recently witnessed. Klein's philosophy on art revolved

around eliminating lines and the boundaries that contain and segregate

humanity. He believed that "line divides and obstructs the pure space of

cosmic sensibility, while colour asserts the freedom and fullness of space"

(McEvilley 239). In this light, Klein's monopinks symbolize the cosmic

embrace, the love inherent in hope and faith, and the freedom that this

hopefulness enables.

Part

II: Interplay

Part

II: Interplay