| |

Klein

and Judo - Julian Haladyn

Klein

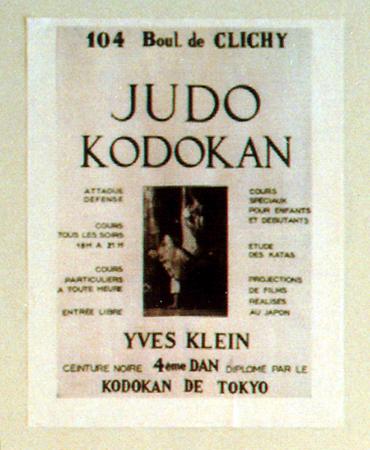

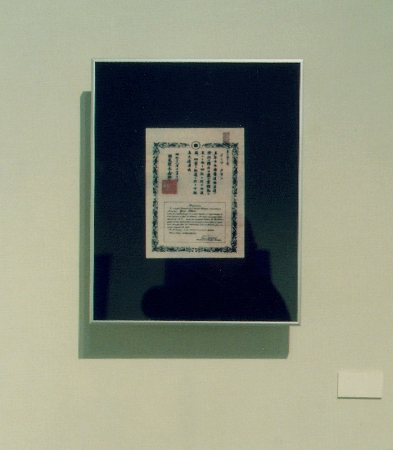

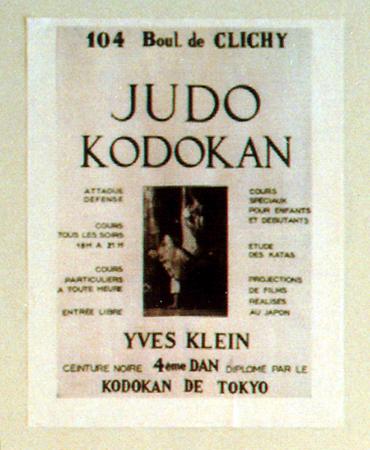

began studying judo in September, 1947, while living in Nice. Although

he was not originally gifted in the art, Klein's obsessive persistence

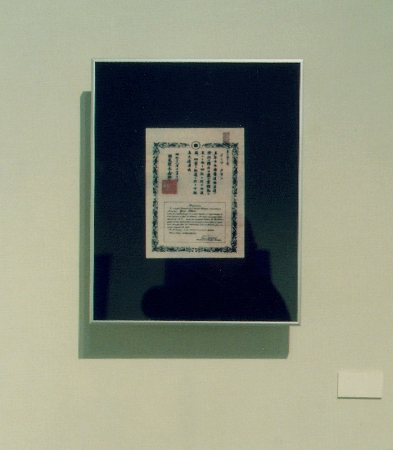

would allow him not only to excel, but eventually to achieve a fourth dan

black belt from the acclaimed Kodokan school in Tokyo, on December 14,

1953, at the age of twenty-five. The importance judo played in Klein's

artistic and social development was extreme; "The self-discipline of judo

structured his personality, and gave him, along with mastery of himself,

the faculties of concentration, impregnation, and recovery on which his

whole method of sensitivity rests." (15 Restany) These faculties which

Klein learnt through his studies in judo where to be the foundation of

his artistic practices, on which he would develop his philosophy of life. Klein

began studying judo in September, 1947, while living in Nice. Although

he was not originally gifted in the art, Klein's obsessive persistence

would allow him not only to excel, but eventually to achieve a fourth dan

black belt from the acclaimed Kodokan school in Tokyo, on December 14,

1953, at the age of twenty-five. The importance judo played in Klein's

artistic and social development was extreme; "The self-discipline of judo

structured his personality, and gave him, along with mastery of himself,

the faculties of concentration, impregnation, and recovery on which his

whole method of sensitivity rests." (15 Restany) These faculties which

Klein learnt through his studies in judo where to be the foundation of

his artistic practices, on which he would develop his philosophy of life.

The main tenet of judo is

"to make the most efficient use of mental and physical energy." (16 Kano)

This is taught in judo using two basic methods: Kala and Randori. Kala,

which means "form", is a system of prearranged movements which the student

learns and preforms in front of teachers and other students; these movements

are meant to teach the student the foundations of attack and defence. Randori,

which means "free practice", is a time to practice the techniques which

the student has learnt, where students are paired off and spar with each

other, as would happen in a real judo match or confrontation. "The objective

of this systematic physical training is to perfect control over the mind

and body and to prepare a person to meet any emergency or attack, accidental

or intentional." (22 Kano) These same two methods can be seen in Klein's

artistic process, with kata being related to ritual and randori being related

to performance.

The

rituals associated with Klein's works - such as the ingesting of the blue

cocktail before entering Le Vide or the bunting of the receipts after the

purchase of that void - are meant to teach the 'reader" of his works the

language he is using to express his vast ideas, preparing them for, or

inaugurating them into, the experience wlnch Klein has arranged for them.

As in the kata, these rituals strengthen the mind's ability to adapt and

respond to unknown stimuli through the continual repetition of certain

key elements; once these elements have been presented enough they become

second nature, one no longer has to "think" about them to be aware of them.

Klein's ritualistic use of the I.K.B. serves this fluiction, where after

seeing enough blue monochromes one no longer "thinks" of the blue, this

allows the mind to ftrrther investigate what is being presented. And what

is left once one takes away the external blue of the monochromes, or for

that matter the walls of Le Vide? What the viewer is left with is themselves.

In the case of leVide the ritual performed before entering the void room

makes one more open to experience the unexpected lack of external stimulation

as a potential rather than a drawback. The potential I believe Klein presented

was simply the possibility of experiencing ourselves in a new way. By giving

nothing external to relate to, he is asking us to project ourselves upon

the whiteness of the walls, much like a movie is projected upon a white

screen. After the kata has been practiced, giving the student the tools

with which to attack and defend, then the student begins randori. The

rituals associated with Klein's works - such as the ingesting of the blue

cocktail before entering Le Vide or the bunting of the receipts after the

purchase of that void - are meant to teach the 'reader" of his works the

language he is using to express his vast ideas, preparing them for, or

inaugurating them into, the experience wlnch Klein has arranged for them.

As in the kata, these rituals strengthen the mind's ability to adapt and

respond to unknown stimuli through the continual repetition of certain

key elements; once these elements have been presented enough they become

second nature, one no longer has to "think" about them to be aware of them.

Klein's ritualistic use of the I.K.B. serves this fluiction, where after

seeing enough blue monochromes one no longer "thinks" of the blue, this

allows the mind to ftrrther investigate what is being presented. And what

is left once one takes away the external blue of the monochromes, or for

that matter the walls of Le Vide? What the viewer is left with is themselves.

In the case of leVide the ritual performed before entering the void room

makes one more open to experience the unexpected lack of external stimulation

as a potential rather than a drawback. The potential I believe Klein presented

was simply the possibility of experiencing ourselves in a new way. By giving

nothing external to relate to, he is asking us to project ourselves upon

the whiteness of the walls, much like a movie is projected upon a white

screen. After the kata has been practiced, giving the student the tools

with which to attack and defend, then the student begins randori.

Klein's

performances are his "free practice", where he is able to try out his ideas

on a Klein's

performances are his "free practice", where he is able to try out his ideas

on a

willing audience. It is

of little importance whether or not the viewer likes or dislikes the work

they experience, Klein's main concern is that they open themselves up to

the potentials inherent in what he is presenting. All of Klein's work is

"aimed at expanding and intensitying human awareness of the actualities

of existence. Above all, he wanted to awaken an individual's sensibility

- one's capacity to see, feel, and think - especially as this might enrich

one's experience of the most fundainental, primal elements that are the

nourishing agents of life and the universe." (7 Stich) Unlike in the paintings

of Malevich, with whom Klein has often been compared, there is no symbolic

meaning inherent in his use of blue which the viewer is suppose to interpret

in order to uncover the "true" meaning of the work. As Klein himself states:

"The object of art is not the painting (i.e., another object), but life

(i.e., a universal principle)." (7 Restany) lii this way the work of art

becomes merely a reference point from which to begin experiencing, and

not the end in itself. What Klein continually shows in his work are traces

of real experience, his pre-arranged kata's, and the viewer is then able,

once the work has been made public, to interact or spar with it. One work

which particularly addresses this is the Anthropometrv performance, where

"traces" of reality are literally printed on the canvas using the real

object - as opposed to the traditional method which produces a simulacra

of the object using fabricated utensils, which have little or no relation

to the object being depicted. Klein said:

"the time of the

brush had ended and finally my knowledge ofjudo was gomg to be useful.

My models were my brushes. I had them smear themselves with colour and

imprint themselves on the canvas.. But this was only the first step. I

thereafter devised a sort of ballet of girls smeared on a grand canvas

which resembled the white mat ofjudo contests." (171-2 Stich)

This explicit reference made

to randori illustrates the impact it had upon Klein's sensibility.

The simplicity of means used

by Klein to express his ideas leads back to the niain tenet of judo, using

both mental and physical energy enough, but not too much, to accomplish

what is needed From judo Klein learned to look for the most direct course

of action, to consider carefully, and then act decisively and without hesitation.

And it is this philosophy that I believe formed the foundations of Klein's

artistic productions.

|

|

Klein

began studying judo in September, 1947, while living in Nice. Although

he was not originally gifted in the art, Klein's obsessive persistence

would allow him not only to excel, but eventually to achieve a fourth dan

black belt from the acclaimed Kodokan school in Tokyo, on December 14,

1953, at the age of twenty-five. The importance judo played in Klein's

artistic and social development was extreme; "The self-discipline of judo

structured his personality, and gave him, along with mastery of himself,

the faculties of concentration, impregnation, and recovery on which his

whole method of sensitivity rests." (15 Restany) These faculties which

Klein learnt through his studies in judo where to be the foundation of

his artistic practices, on which he would develop his philosophy of life.

Klein

began studying judo in September, 1947, while living in Nice. Although

he was not originally gifted in the art, Klein's obsessive persistence

would allow him not only to excel, but eventually to achieve a fourth dan

black belt from the acclaimed Kodokan school in Tokyo, on December 14,

1953, at the age of twenty-five. The importance judo played in Klein's

artistic and social development was extreme; "The self-discipline of judo

structured his personality, and gave him, along with mastery of himself,

the faculties of concentration, impregnation, and recovery on which his

whole method of sensitivity rests." (15 Restany) These faculties which

Klein learnt through his studies in judo where to be the foundation of

his artistic practices, on which he would develop his philosophy of life.

The

rituals associated with Klein's works - such as the ingesting of the blue

cocktail before entering Le Vide or the bunting of the receipts after the

purchase of that void - are meant to teach the 'reader" of his works the

language he is using to express his vast ideas, preparing them for, or

inaugurating them into, the experience wlnch Klein has arranged for them.

As in the kata, these rituals strengthen the mind's ability to adapt and

respond to unknown stimuli through the continual repetition of certain

key elements; once these elements have been presented enough they become

second nature, one no longer has to "think" about them to be aware of them.

Klein's ritualistic use of the I.K.B. serves this fluiction, where after

seeing enough blue monochromes one no longer "thinks" of the blue, this

allows the mind to ftrrther investigate what is being presented. And what

is left once one takes away the external blue of the monochromes, or for

that matter the walls of Le Vide? What the viewer is left with is themselves.

In the case of leVide the ritual performed before entering the void room

makes one more open to experience the unexpected lack of external stimulation

as a potential rather than a drawback. The potential I believe Klein presented

was simply the possibility of experiencing ourselves in a new way. By giving

nothing external to relate to, he is asking us to project ourselves upon

the whiteness of the walls, much like a movie is projected upon a white

screen. After the kata has been practiced, giving the student the tools

with which to attack and defend, then the student begins randori.

The

rituals associated with Klein's works - such as the ingesting of the blue

cocktail before entering Le Vide or the bunting of the receipts after the

purchase of that void - are meant to teach the 'reader" of his works the

language he is using to express his vast ideas, preparing them for, or

inaugurating them into, the experience wlnch Klein has arranged for them.

As in the kata, these rituals strengthen the mind's ability to adapt and

respond to unknown stimuli through the continual repetition of certain

key elements; once these elements have been presented enough they become

second nature, one no longer has to "think" about them to be aware of them.

Klein's ritualistic use of the I.K.B. serves this fluiction, where after

seeing enough blue monochromes one no longer "thinks" of the blue, this

allows the mind to ftrrther investigate what is being presented. And what

is left once one takes away the external blue of the monochromes, or for

that matter the walls of Le Vide? What the viewer is left with is themselves.

In the case of leVide the ritual performed before entering the void room

makes one more open to experience the unexpected lack of external stimulation

as a potential rather than a drawback. The potential I believe Klein presented

was simply the possibility of experiencing ourselves in a new way. By giving

nothing external to relate to, he is asking us to project ourselves upon

the whiteness of the walls, much like a movie is projected upon a white

screen. After the kata has been practiced, giving the student the tools

with which to attack and defend, then the student begins randori.

Klein's

performances are his "free practice", where he is able to try out his ideas

on a

Klein's

performances are his "free practice", where he is able to try out his ideas

on a