1. Oxfordshire OaksDe(con)structing the image icon STEVE LYONS |

“The lone tree is the great ancient symbol of the mortal individual, rooted in the totality of nature yet suffering its solitary destiny.” (20)

- Jeff Wall, from “Into the Forest” (1994)

Referencing the iconic image of the lone tree in Rodney Graham’s Oxfordshire Oaks (1990), artist and critic Jeff Wall considers the politics embedded in the British Columbia landscape. Rodney Graham, a so-called Vancouver School photoconceptualist, has (since the late 1970s) investigated these politics of landscape, implicating his artwork in a complex body of social, political, literary, and theoretical issues. In Oxfordshire Oaks, a series of large-format monochrome colour photographs, Graham reinterprets a quintessential ‘image icon’ of nature, the solitary tree in a rural landscape, simply by inverting the image. Graham presents the viewer with the task of disentangling meaning and deriving narratives from a simple yet evocative gesture. Meaning in Oxfordshire Oaks can be generated through the interplay of many perspectives. By presenting a body of work that legibly functions through multiple symbolic viewpoints, Graham ultimately helps to deconstruct the myth of the ‘image icon.’ In the following essay, I will explore three distinct perspectives: regional, scientific/historical, and linguistic, in order to demonstrate the complexities of signification in Graham’s Oxfordshire Oaks.

REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Within the context of British Columbia, Wall situates Graham’s images of the lone tree at the forefront of current political concerns, writing that,

The masters of B.C.’s semi-colonial, natural resource-based economy regard the natural world as simply an obstinate material form of future money which must be transmuted into real money as quickly as possible. The standing tree is an affront to these ‘owners of nature,’ whose totem poles must lie in piles on trucks. (19)

For Wall, the lone tree is not only symbolic of the mortal individual, but also exists as a reminder of the mortality of British Columbia’s once abundant natural resources. In this way, the lone tree, as photographed by Rodney Graham, becomes a political entity, an illustration of inversion which contemplates ‘inverted’ progress. Standing in clear-cut farmland, the solitary tree is the last remaining vestige of a once lushly forested region, which will soon be sacrificed for the sake of capital gain and economic prosperity. Each of Graham’s Oxfordshire Oaks connotes great economic potential for British Columbia at the expense of its natural resources. Viewed solely as a priced commodity, the tree loses all cultural and environmental value (its links to heritage and nature respectively).

Through his discussion of the cultural repercussions implicit in the lone tree, Wall unearths the subversive implications of Graham’s superficially conservative landscape photographs. The flat, vast planes and uninterrupted horizons on which Graham’s solitary trees are found, though more naturally associated with the landscapes of the Canadian prairies, are indeed plots of farmland in British Columbia. This shocking realization, which subverts the usual association of natural abundance in British Columbia, is purposely subverted in Graham’s Oaks. Consequently, the projection of prairie-scapes onto the west-coast generates a particular dystopian narrative. The lone trees in Oxfordshire Oaks reflect upon a specific history of forestry in British Columbia. They are visual reminders of a past forest. ‘Rural’ (within the context of British Columbia) does not appear natural. It conflicts with the constructed regional identity as it is ideologically rooted in deforestation, in the destruction of a provincial consciousness for the production of financial gain. While documenting the existing landscapes in British Columbia, Graham also attempts to project the viewer into a future British Columbia, one in which the solitary tree serves as a reminder of the forests that “once were” and that “could have been.”

SCIENTIFIC/HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

From a regionally specific perspective, the lone tree is emblematic of the problem of deforestation. However, due to the conceptual versatility of Oxfordshire Oaks, meaning shifts when approached from a different standpoint. Issues pertaining to the depletion of natural resources are abandoned when viewed through the scientific and historical framework of these photographs. In a statement about Oxfordshire Oaks, Graham writes, “I was thinking about it [the inverted lone tree] as an iconic image, something you would see in a text book illustrating the idea of the inversion of an image in general, showing the mechanism of the optics of the eye” (23). Graham refers here to the optical geometry prevalent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In exhibiting inverted images of trees, Graham presents the viewer with a historical construction of vision. Jonathan Crary labels this early conception of the observer the ‘camera obscura model of vision’: “the camera obscura performs an operation of individuation; that is, it necessarily defines the observer as isolated, enclosed, and autonomous within its dark confines” (38-39). Within the camera obscura model, the viewer is bound to a fixed relationship with the world. In other words, the viewer functions not through ‘reality,’ but within a mediated representation of this reality. When Graham situates Oxfordshire Oaks in this history of objective vision and scientific ‘truth,’ the lone tree functions as a tabula rasa, and the image’s inversion becomes the focal point of the viewer’s attention. Thus, through this scientific approach, the lone tree is used for the sole purpose of addressing greater problems concerning vision, the observer, and visual representation. In the scientific and historical perspective, the focus shifts away from the ‘tree’ as a subject towards an investigation into questions of perception and optical experience.

In a 1979 work entitled Camera Obscura, Graham more aggressively probes the mediated ‘camera obscura model of vision’ proposed by Crary. Graham writes, “I made an actual camera obscura for the purpose of installing it in a landscape so that an inverted image of a tree would be realised on a screen inside it” (23). In Camera Obscura, the viewer walks in and out of this apparatus, but the image he/she is confronted with is forever at the moment of representation. Thus, Graham effectively lays bare the process of mediation by presenting an image in a perpetual state of conception. As opposed to Camera Obscura, the inversion of the image in Oxfordshire Oaks functions symbolically, presenting a metaphor for the photographic process and the mediated image. While Camera Obscura phenomenologically demystifies the process of mimetic representation, Oxfordshire Oaks requires intellectual reasoning to invoke the historical understanding of the human eye within the traditional media of analog photography. Moreover, Graham situates Oxfordshire Oaks in a history of criticism of ‘visual truth,’ crossing the boundaries of scientific textbook illustrations and cultural theory to reveal a new understanding of photographic ‘reality.’

LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE

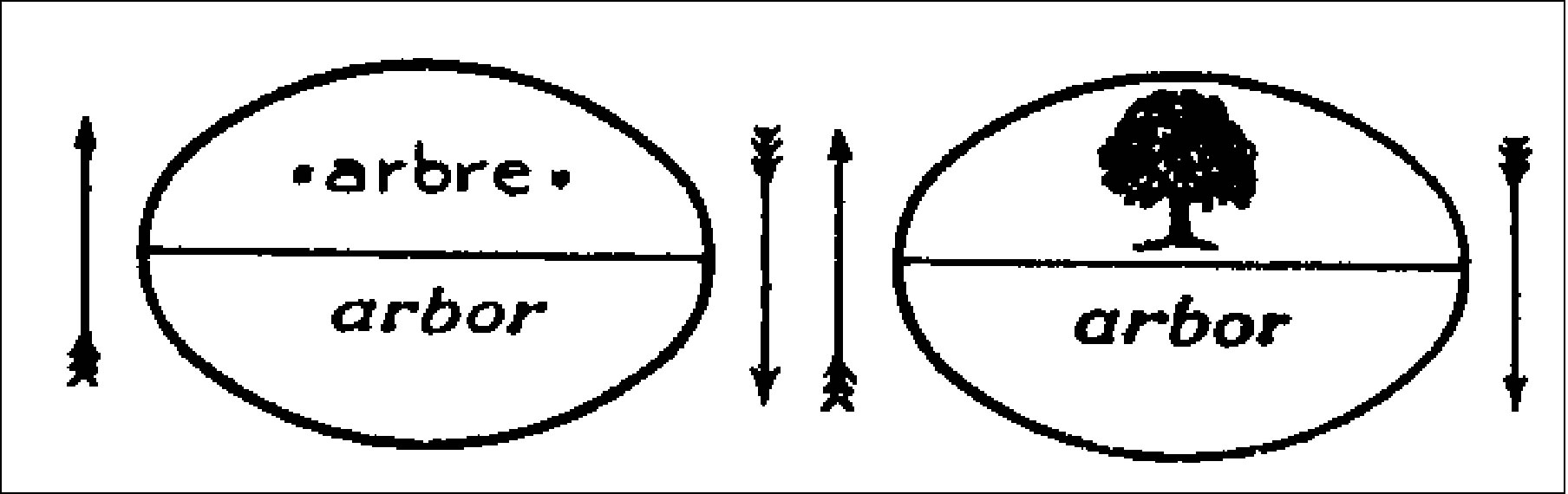

Though the scientific/historical perspective ties Oxfordshire Oaks to concepts of visual truth in representation, it fails to account for the lone tree’s specific textual references. The icon of the lone tree has been used, most notably, in Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics (1916).

Illustration, Course in General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure

The dialectic formed between Saussure’s tree and Graham’s oaks introduces issues of language within visual art. Jeff Wall speculates upon the significance of the lone tree in Oxfordshire Oaks: “Saussure’s little drawing of a tree was used as a universal sign in a discussion of the relation between signifier and signified. Its universality was assumed: all humans know what a tree is, hence its image can refer not only to itself, but to the concept of an image in general” (21). When Graham appropriates this icon of structural linguistics in Oxfordshire Oaks, he overtly projects visual art into Saussure’s semiotic construction of ‘language.’ Within this linguistic framework, visual art becomes a ‘text’ to be ‘read’ according to the ‘signs’ within the work. The visual ‘signifiers’ of the image combine with the ‘signified’ represented by the perceptual understanding of the individual viewer to create meaning. Graham’s art becomes overtly self-reflexive when projected into the frame of structural linguistics. Furthermore, we, as viewers, are challenged to derive signs from a relatively small number of visual signifiers (such as the lone tree, its inversion, the rural backdrop, the medium of photography). However, since the image can be iconic in multiple contexts, and may be ‘read’ differently by different people, we are confronted with a multiplicity of subjective meanings from a seemingly simple image. Oxfordshire Oaks reproduces the iconic image of semiotic discourse in order to investigate the complicated relationship between art and language. When considered from a linguistic perspective, Oxfordshire Oaks exposes the process of ‘reading’ a work of art as a text.

THE CO-EXISTENCE OF MEANING

The various ways in which Graham’s Oxfordshire Oaks function as iconic reveal the mechanisms behind the myth of the ‘image icon.’ From a regional perspective, Oxfordshire Oaks presents a critique of the current problem of deforestation in British Columbia. Scientifically/historically, these photographs directly address an anxiety about mediated perception as optical ‘reality.’ Finally, Graham’s exploration of a linguistic approach to the image reveals possibilities of ‘reading’ the lone tree as a ‘text’ that can render multiple interpretations outside the seeming singularity of meaning attributed to the ‘image icon.’ Thus, Oxfordshire Oaks, in its deceptive simplicity, speaks to a wide range of topics from separate fields of study. By creating a work with multiple points of access (through established research and knowledge), Graham allows the viewer to navigate these meanings in response to his or her own unique perspective. Graham constructs a conceptual maze, where each viewer ‘walks’ independently, but must process through a set of predetermined discursive frameworks. The artist thereby permits a controlled subjective reception -- an illusion of the liberated viewer. In essence, Oxfordshire Oaks deconstructs the image icon’s claim of universal meaning by exposing these directed and varied views of a quintessential image icon.

In addition to these guided individual interpretations, Graham saturates his work in layers of theoretical, literary, historical, and cultural meaning, which the knowledgeable viewer may decipher. These meanings manifest themselves in a seemingly simple and coherent body of photographs. In offering legible yet disparate readings of his work, Graham poses an exercise in cognitive self-awareness. The work’s multiple meanings co-exist for the ‘ideal’ viewer, which makes them largely inaccessible to most viewers. However, these many meanings are not interdependent. That is, the viewer can be aware of the various meanings of the work while extrapolating from just one. Thus, a project like Oxfordshire Oaks is fundamentally intellectual in its reception. Graham calls on the viewer to recognize the myth of ‘universal meaning’ by acknowledging that there is no such world-wide collective truth. Truth, for Graham, is the harmonious co-existence of meaning.

Works Cited

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990.

Graham, Rodney. “Oxfordshire Oaks, 1990.” Rodney Graham. London: Whitechapel, 2002. 23.

Wall, Jeff. “Into the Forest.” Rodney Graham: Works from 1976 to 1994. Eds. È. Van Balberghe and Y. Gevaert. Toronto: Art Gallery of York University, 1994. 11-25.

|

||

| Steve Lyons is a fourth year studio art student in the Visual Arts Department at the University of Western Ontario. His major research interests lie in the intersections between contemporary visual art and the “cinematic experience.” |