| Back to show catalogue | ||

|

The Ill-Fated Obelisk - Sophie Brodovitch

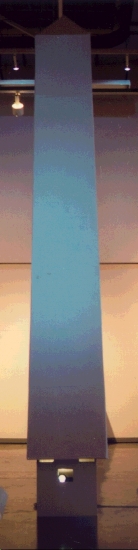

Generally made of granite or basalt, the obelisks took thousands upon thousands of men to build and transport. The general consensus by scholars is that the obelisks were carved directly out of the stone at designated rock quarries. Because of the enormous amounts of work that were required to build and transport the monuments, their associations with power and royalty became even greater. The obelisk provided the rulers with symbols of strength and prestige. Not only this, they could also have stories inscribed upon them in order to immortalize the king. The obelisk was essentially the ultimate way for the ruler to promote his or her power. The obelisk in Paris was the first to be moved into modern Europe. Finally erected in La Place de la Concorde on October 25, 1833, the obelisk stands as a reminder of the greatness of ancient civilizations, as well as the connection between the French and the ancient gods and rulers. The obelisk was originally set before the Luxor Temple (Habachi, p.164), but were moved as a result of political issues occurring at the time. The campaign to move the monument from Egypt to Paris was long and difficult, lasting many years. Finally, the obelisk was raised in the Place de la Concorde, sealing the bond between France and ancient Egypt. With this knowledge of the history of the obelisk, it is not surprising that Yves Klein would come to attempt to create a work involving one of the most famous monuments in the world, particularly one continuously associated with gods, rulers and kings. Klein's Blue Obelisk was to be an illumination of the Egyptian obelisk at the place de la Concorde by putting blue filters over the spotlights that usually lit up the monument. In addition to this, he wanted to elevate the base by lifting it with a metal rod (Stich, p. 93). Klein's Blue Obelisk was a part of Yves Klein's second blue exhibition from May 14-23, 1957 at the Galleria Colette Allendy. The exhibition included works such as the Pigment pur, Tapisserie bleue, Disque bleu, and Sculpture bleue (Stich, p.93-95). The gallery was literally filled with Klein's blue creations. Each work explored different aspects of the blue sensation, allowing for a fuller, more intense experience of Klein's works. Therefore, it is not surprising that Klein wanted to include something beyond the gallery space, something that would allow him to reach the people who could not attend the show. Due to the selection of the works in the Allendy exhibit, Klein's idea for the illumination of the Blue Obelisk is even more understandable as Klein would have wanted to further develop his ideas surrounding the blue, particularly beyond the exhibition space. According to Stich, the Allendy exhibit "...included the seeds for almost all of the concepts that Klein would develop as signatures of his art." (Stich, p.97). In this context, the illumination of the monument could be seen as a pre-cursor for future works that involve the saturation of the world in blue, for example the blue atomic explosion, or even the dyeing blue of the sea. These notions all embody Klein's dream of the Blue Revolution, which would provide him with some type of claim to the world through I.K.B.. Furthermore, through simple reference to Klein's ego, it seems a logical choice that Klein would try to create a work that would allow him to claim ownership of a historically famous monument, even if only for a few minutes. Indeed, Klein's choice of the obelisk as the object of his illumination is not surprising. The place de la Concorde, probably one of the most famous squares of Paris, is located at the end of the Champs Elysees. The neighbourhood alone would have automatically provided Klein with a large audience, while the physical act of the illumination would have reached far more people visually, again allowing for a greater audience. As well, the obelisk and all of its symbols and ancient meanings provided Klein with an enormous amount of notions with which to play around. He would have been able to create an association between himself and the I.K.B. to historical characters dating back to ancient Egypt. Klein would have also been interested in the ancient belief that the obelisk "...reached, pierced, or mingled with the sky...", suggesting that the obelisk connected the earthly world to the heavenly realm of the unknown above. Klein's thoughtfulness in terms of the choice of medium and the location of the illumination would have been enough to open up his works to further interpretations, if not simply enough to create quite a stir.

Klein also insured that this work would not be missed by illuminating the

structure in blue as opposed to painting it blue. This is significant

because it demonstrates that Klein was trying to use the colour blue to

achieve a different purpose other than a primarily visual experience in

terms of the viewer and the object

"To make it absolutely clear that I am abandoning material and physical Blue, waste and coagulated blood issued forth from the raw material sensibility of space, I want to obtain authorization from the Prefecture of the Seine and the Electricite de France to illuminate in Blue the obelisk on the place de la Concorde..."

From a phenomenological point of view, Klein's Blue Obelisk allows the viewer a visual interaction that moves beyond looking simply at the object. The viewer is dealing with the lights, which project an experience entirely of their own. In addition to this, the lights are focused on the obelisk itself, which is also another viewing experience. By offering or suggesting several ways of looking at the work, Klein pushes the viewer to use his or her maximum senses when viewing the Blue Obelisk. Klein also manipulates how the viewer sees by using the obelisk itself. For many Parisians, this would have been a monument that they may have seen frequently. By altering the way that it is usually seen, Klein further pushes the observer's way of looking at it. Klein allows the viewer to see the obelisk in a new light, both literally and figuratively speaking.

Unfortunately, the obelisk was never lit up as part of the exhibition as

it was deemed to be "...overly personal..." (Stich, p.139). Much

to Yves Klein's dismay, the illumination of Blue Obelisk would be limited

to the trial run done with Iris Clert. However, simply from a basic

understanding of Klein and his works, Klein's illumination of the obelisk

fulfilled all of his needs, it truly embodied the notion of Klein's work

as a lived experience. Not only was Klein able to claim the ancient

monument as his own, he was also able to claim all of the space surrounding

it that was touched by the blue lights. Although not to the same

extent of the Blue Atomic Explosion, the lighting of the obelisk allowed

Klein to saturate the air with blue. Anything that crossed in the

shadows became a part of the work, Klein had managed to make the ultimate

"blue experience" by causing the willing or unwilling participation of

the observer. Had the illumination taken place, for a few moments

Klein would have changed the viewers into observers, and finally into participants,

thus fulfilling the phenomenological notion of perception and observation

as a lived experience.

Bibliography Habachi, Labib. The Obelisks of Egypt. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1977. Stich, Sidra. Yves Klein. Ostfildern: Cantz Verlag, 1994. |

||

The ancient great civilizations left us numerous clues to their way of

life, most of which refer to their triumphs and achievements. Among

these ancient remnants, the obelisk remains to be one of the most famous.

A symbol of strength, skill, and might, the obelisk was considered by the

Egyptians to be sacred to the sun god Re (Habachi, p.4). Although

originally the obelisk may have been a sacred monument designed as an offering

to the gods, it has since been seen and used in many different contexts.

Indeed, some obelisks may have celebrated royal victories, while

others were built and erected as offerings to the gods. Ultimately

however, the obelisk provided a means for the king to link himself to the

gods. For example, on one obelisk erected by Ramsesses II, it is

written "His power is like that of Monthu [the god of war], the bull who

tramples the foreign lands and kills the rebels". On many other obelisks,

the king is depicted at the top, making direct offerings to the gods.

The ancient great civilizations left us numerous clues to their way of

life, most of which refer to their triumphs and achievements. Among

these ancient remnants, the obelisk remains to be one of the most famous.

A symbol of strength, skill, and might, the obelisk was considered by the

Egyptians to be sacred to the sun god Re (Habachi, p.4). Although

originally the obelisk may have been a sacred monument designed as an offering

to the gods, it has since been seen and used in many different contexts.

Indeed, some obelisks may have celebrated royal victories, while

others were built and erected as offerings to the gods. Ultimately

however, the obelisk provided a means for the king to link himself to the

gods. For example, on one obelisk erected by Ramsesses II, it is

written "His power is like that of Monthu [the god of war], the bull who

tramples the foreign lands and kills the rebels". On many other obelisks,

the king is depicted at the top, making direct offerings to the gods.

As in the Leap Into the Void, the Blue Obelisk allowed Klein move into

the void. Although the works are different in terms of their approaches

to the reaching the void, both works attempt to confront the issue of movement,

whether psychological or physical, into a space unknown. The Blue

Obelisk allowed Klein to address issues of immateriality, a notion that

was fundamental to the Allendy exhibition (Stich, p.92). Through

the blue lights, the world becomes the art work, as well as the medium.

Without air or the objects in the surrounding area, including the obelisk

itself, the illumination would not have been possible. The complete

saturation of the area served to bathe the world in a new type of medium,

that of light. This allowed Klein to make the art-making ingredient

(as referred to by Stich) immaterial and undefinable because it could not

be held, moved or grasped. This work depended entirely on the moment

and could never be truly reproduced, not even on film.

As in the Leap Into the Void, the Blue Obelisk allowed Klein move into

the void. Although the works are different in terms of their approaches

to the reaching the void, both works attempt to confront the issue of movement,

whether psychological or physical, into a space unknown. The Blue

Obelisk allowed Klein to address issues of immateriality, a notion that

was fundamental to the Allendy exhibition (Stich, p.92). Through

the blue lights, the world becomes the art work, as well as the medium.

Without air or the objects in the surrounding area, including the obelisk

itself, the illumination would not have been possible. The complete

saturation of the area served to bathe the world in a new type of medium,

that of light. This allowed Klein to make the art-making ingredient

(as referred to by Stich) immaterial and undefinable because it could not

be held, moved or grasped. This work depended entirely on the moment

and could never be truly reproduced, not even on film.